The Microbiologist went through the story and the said “okay, you can stop the antibiotics”.

“But the guidelines say we should give seven days”, replied the doctor.

“Yes, but the patient is better” replied the Microbiologist.

“So why do the guidelines say seven days then” persisted the doctor.

Good point thought the Microbiologist…

So why do we have defined durations for courses of antibiotics? Why do these appear to be carved in stone so that no doctor or patient dares to deviate from the principal of “you must finish the course of antibiotics”? Surely the correct length of course is whatever makes the patient feel better?

Where does the argument that you must finish the course come from?

I can remember as a child being indoctrinated with the idea that if I didn’t take the full course of a foul tasting antibiotic solution then I would come to harm, and yet again at school this is what we were taught. Moving on to medical school and working as a junior doctor I remember being told this as though it was gospel and that I must make sure every patient I saw understood this principal.

The authors of the BMJ paper go right back to the beginning of the antibiotic era to demonstrate where the idea of a course of antibiotics comes from. They mention Howard Florey’s team’s experience of a patient dying from staphylococcal septicaemia because the penicillin they were using (and recovering from the patient’s urine to give to him again) ran too low and the infection got worse again and he died. They also mention Alexander Fleming’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1945 in which he envisaged a patient inadequately treated with antibiotics passing on a resistant bacterium to his wife who subsequently died from an infection with this resistant bacterium… you can see why ideas like this from the “experts” might fuel the idea that “you must finish the course or else…”.

So basically the old arguments FOR finishing the course are:

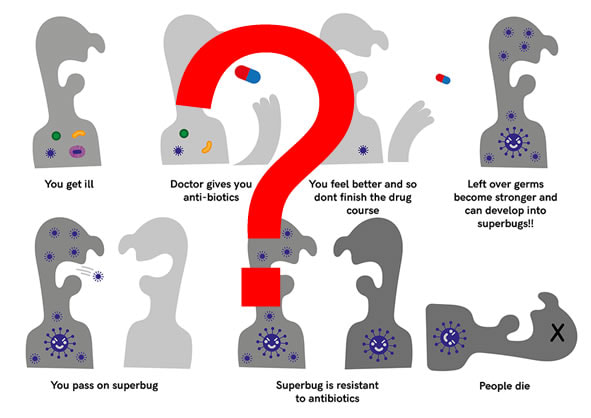

1. Incomplete courses of antibiotics lead to antibiotic resistance

2. Incomplete courses of antibiotics lead to patient harm

Do shorter courses of antibiotics cause resistance?

In a nutshell, NO, there is no evidence that shorter courses of antibiotics lead to resistance. The main drivers for antibiotic resistance are low doses of antibiotics and prolonged courses of antibiotics.

It has been known for many years that if you want to make a bacterium resistant in a laboratory setting the best way to do this is to “passage” a culture of bacteria through gradually increasing concentrations of antibiotic. The low doses of antibiotics allow the bacteria to survive by adapting and mutating in order to overcome the antibiotic’s mechanism of action thereby becoming resistant.

This process is what happens when resistance occurs during treatment of bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Neisseria gonorrhoea and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

Prolonged courses of antibiotics also lead to antibiotic resistance by wiping out a patient’s antibiotic sensitive normal flora permitting antibiotic resistant bacteria to colonise the patient and become the patients “new” normal flora. Antibiotic resistant bacteria can be transmitted to other people who won’t know they have a resistant bacterium until it causes an infection. When the patient then develops an infection it is these antibiotic resistant bacteria which are the cause.

For example, a patient might be given an inappropriately long course of Amoxicillin for a Streptococcal throat infection which kills off any bacteria in their normal flora sensitive to Amoxicillin. This might include the E. coli in their gastrointestinal tract which then allows a newly acquired Amoxicillin resistant E. coli to move in. A few weeks later the patient develops a urinary tract infection with E. coli but rather than this being sensitive to Amoxicillin it is the resistant E. coli.

Shorter courses of antibiotics are less likely to cause as much damage to the patient’s normal flora because the bacteria have less total exposure to antibiotics. Shorter courses are therefore less likely to allow antibiotic resistant bacteria to become part of the patient’s normal flora.

Another argument I often give to students and junior doctors to try and dispel the myth about finishing the course of antibiotics is that doctors already don’t finish courses! Consider this, your patient is admitted with what is thought to be pneumonia and you start treatment for pneumonia with something like Amoxicillin PLUS Clarithromycin BUT the chest x-ray comes back completely normal and the urine shows the patient has a UTI. You CHANGE the treatment to Trimethoprim and stop the Amoxicillin PLUS Clarithromycin… don’t you? Surely you don’t continue treating the pneumonia just because “the patient must finish the course”, no you STOP them.

I use this scenario to argue that if a patient is started on antibiotics but is subsequently shown to not have an infection then it is okay to stop the treatment; likewise it could be used to argue that if a patient is started on antibiotics and gets better before the “course” has finished then it is okay to stop the antibiotics; as they no longer have an infection they don’t need antibiotics!

Do short courses of antibiotics cause treatment failure and harm?

This is a hard question to answer because there is very little evidence, however absence of evidence does not necessarily mean evidence of absence. Interestingly when I started as a junior, treatment duration for CAP was 10-14 days but over the years treatment durations for many infections have reduced. Now CAP is treated for 7 days without any harm coming to patients, although I’m unaware of the vast body of evidence to suggest this change. I suspect it is more as a result of what individual doctors have tried rather than randomised controlled double-blinded studies. It may be the case that in a few more years the standard duration for CAP is in fact 3 or 5 days.

It is probably very difficult to do these randomised controlled double-blinded studies as both healthcare professionals and patients are so indoctrinated in the belief that shorter courses of antibiotics lead to worse outcomes. Who would consent for a study which might deliberately give them a short course of antibiotics! Would you want the shorter course?

Ha ha, I’d only agree if I thought the shorter course was an appropriate treatment in the first place!! For example, I think a 5 day course for pneumonia rather than 7 days would work for most people but in my opinion 3 days treatment for UTI maybe already be too short (or maybe I just see those who fail treatment and require longer courses). Clearly there is still work to be done in convincing people, including this Microbiologist.

It could be proposed that GPs only give 3 days of antibiotics and ask the patient to return to be reassessed. However, this would not create the randomised controlled double-blinded studies and evidence to back up this proposal. It also has the problems that patients believe more is better, they might not want to return, the GP might not want to book up a clinic with repeat visits, the patient wouldn’t want to pay twice for two prescriptions etc.

I think one of the things we also need to remember is that the natural tendency of most infections is to get better; antibiotics may reduce the duration of symptoms, make the patient feel better faster or allow healing of damaged tissue to occur more quickly. It might be that shorter courses of antibiotics, or delayed courses of antibiotics, are able to do this just as well as long courses without the patient coming to harm. Clearly some infections must be treated or the patient will definitely come to harm e.g. meningitis, infective endocarditis, sepsis, but these might be the exceptions rather than the norm.

I think it is fascinating that a paper that proposes using shorter durations of antibiotics for treating infections wants to replace one length of treatment with another different length of treatment. This may be the easiest thing to do because it is simple to understand but this takes away the need to think about how the individual patient is responding. Not all patients are identical and not all antibiotic/bacterium combinations respond in the same way. The trick is to give enough that the patient gets better without giving too much.

So when is it safe to give short courses of antibiotics?

The BMJ paper asks the question about whether we should be giving short courses of antibiotics but it doesn’t provide any specific answers as to when it is safe to give those short courses. One of the ideas the authors have proposed is that patients should be told to take the antibiotics “until they feel better”. Whilst this sounds simple, it is not. What does “until they feel better” mean? Temperature has settled, pain has gone away, swelling has gone down, breathing is back to normal… the list is endless and each patient will have a different idea of what constitutes “better for them”.

Reflecting on my own practice, when I give advice about duration of treatment I weigh up how the patient is responding clinically both subjectively (how they feel) and objectively (how blood tests are changing), the type of infection, my knowledge of how a specific bacterium might respond to shorter durations of treatment, how a longer course might adversely affect the patient’s normal flora, what side-effects the patient might be experiencing and whether there are non-antibiotic aspects to the patient’s treatment e.g. draining abscesses, removing prosthetic material. Unconsciously I tend not to use a one size fits all approach to how I manage patients, but I have many years of experience learning how to do this. To expect non-infection specialists to do the same is possibly unfair and unrealistic. There is a need for a much simpler solution.

So the authors of the BMJ paper have asked the question about whether the concept of a specific course of antibiotics is no longer appropriate and I think this is a great idea. Let’s have the debate. Let’s try to gather the evidence. Is there is a limit to how short we can safely cut a patient’s antibiotic treatment? Let’s see if this approach can help protect the antibiotics we have left and try to stave off the post-antibiotic era.

Reference

The antibiotic course has had its day. Llewelyn M, Fitzpatrick J, Darwin E, et al. BMJ 2017. 358:j3418

PS The other thing I have noted about the BMJ paper is that one of the authors is about to join us as a member of the local microbiology department. It is great to have doctors who are willing to ask the difficult questions so welcome to the team!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed