A recent newspaper headline drew my attention to some work done at Newcastle University, in the UK, where they have discovered bacteria doing something a little bit naughty… stripping!

Bacterial structure

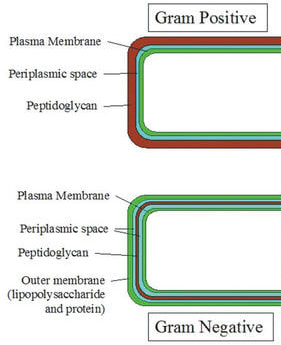

Bacteria contain numerous structures such as a chromosome, ribosomes, mitochondria, etc. which are involved in their day-to-day functioning. They also have a cell wall and sometimes a cell membrane. In fact it is this cell wall structure that dictates whether a bacterium is Gram-positive or Gram-negative.

When is the cell wall a liability?

Most of the time the cell wall is of overall benefit to the bacterium but sometimes the bacterial cell wall becomes a liability. This is usually the case when the bacterium is inside a host. Various components of the host immune system target the cell wall, including chemicals like lysozyme and antibodies against cell wall targets. In fact a number of vaccines have been developed to encourage the human immune system to produce antibodies against cell wall components e.g. pneumococcal vaccine.

Another negative aspect of having a cell wall is that some antibiotics specifically target the cell wall including beta-lactams (penicillins, cephalosporins and carbapenems) and glycopeptides (Vancomycin and Teicoplanin).

Wouldn’t it be great if you were a bacterium and could take off your cell wall when you were under attack and then put it back on when the coast was clear? Cue the music…dada da dada, da…

The bacterial striptease

A team at Newcastle University have shown that bacteria from patients can remove their cell wall and then put it back on again, effectively doing a striptease! They published their findings in Nature Communications with the catchy title of “possible role of L-form switching in recurrent urinary tract infection”… surely “X-rated bacterial striptease (Certificate 18)” would have got more media coverage?

Is this actually new science?

In fact cell wall deficient bacteria are known as L-forms, and they have actually be known about since 1935 when they were first described by a German Microbiologist Emmy Klieneberger-Nobel who was working in London having been expelled from Germany in 1934 for being Jewish. She is most famous for her work with Mycoplasma spp. (which naturally have no cell wall) but during her work she discovered other bacteria that should have had a cell wall but didn’t! She called them L-forms after the Lister Institute of Preventative Medicine where she was working at the time (it’s now part of the University of London). Anyway I digress…

Back to stripping bacteria

In a study looking at bacteria causing “recurrent” UTIs in elderly patients the Newcastle team looked to see if these were in fact “persistent” infections (i.e. they never actually went away) and whether a striptease act (cell wall shedding) might be responsible.

Thirty elderly patients provided a urine sample every 2 weeks over a period of 6 months to give a collection of 360 urine samples. These samples were then passed through a filter which was small enough to stop large cell walled bacteria passing through, but large enough that smaller L-form bacteria could pass through. The filtered urines were then maintained in liquid culture to look for the growth of cell walled bacteria again. The Newcastle team also performed microscopy in the filtered samples to look for L-form bacteria.

In all 46% of samples had L-forms bacteria in them, which could be recovered back to cell wall forms in vitro. This included bacteria such as Staphylococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp. and Pseudomonas spp.

So what about in patients treated with antibiotics; are L-form bacteria responsible for “recurrent” UTIs?

A follow up study by the Newcastle team took samples from a patient who was undergoing treatment for a UTI and filtered these samples. On two occasions, when the patient was being treated with Cefalexin (a cell wall active agent), L-form bacteria were recovered that were genetically indistinct from the original bacterium causing the patient’s UTI. This showed that L-form bacteria “could” be responsible for treatment failures.

What does this mean for clinical medicine?

It’s not clear yet what this really means for clinical medicine. The Newcastle team suggest that the ability to lose the cell wall, and hence an antibiotic target, might be a reason for treatment failures and therefore recurrent or relapsing UTIs. This is possible but in most cases UTIs aren’t treated with cell wall active antibiotics! Most UTIs are treated with antibiotics such as Trimethoprim and Nitrofurantoin or even Gentamicin, none of which target the cell wall, so sorry Newcastle team, relapses in this case would have a different mechanism. It’s certainly worth further study though, as it may be part of a group of methods whereby bacteria can evade effective treatment, and it might also be good to see whether bacteria do this in other parts of the body where treatment with cell wall active antibiotics are often relied upon for these infections e.g. the blood stream and biliary tract infections. It’s fascinating stuff and made me giggle, thinking of nerdy scientists in a strip club watching pole dancing bacteria.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed