Most people, including healthcare workers, think that antimicrobial resistance’s biggest threat is related to our ability to treat common infections such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections or cellulitis, but I think that is incorrect. Don’t get me wrong, it’s still important, but for me it’s not the most important threat from antimicrobial resistance.

Before I tell you what I think the biggest threats are, let me tell why treating common infections isn’t the biggest threat…

Common infections are common. Okay, that’s obvious, but look at it another way. Common infections are SO COMMON that if they had a tendency to kill people then the human race would have died out years ago! There are 15,000x more bacteria on 1 person than there are people on the planet… and that doesn’t even take into account all the other microorganisms in the environment or on other animals… if you don’t like viruses, bacteria, parasites and fungi you’re living on the wrong planet….

We have only had antibiotics for the past 100 years of our existence and yet we have managed to survive and multiply and spread around the World for 6-7 million years before this. The pre-antibiotic era will be essentially the same as an antibiotic resistance era in terms of the treatment of common infections. Common infections have had millions of years to wipe out the human race and yet they haven’t. In fact, the tendency of most infections is to get better without any antimicrobial treatment.

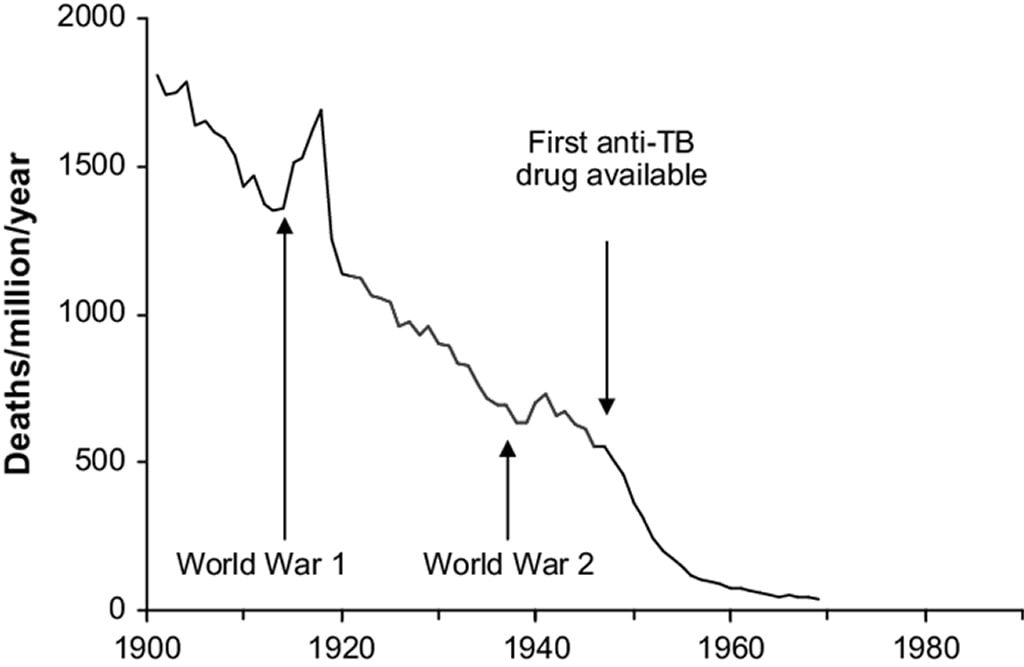

Most of the reduction in illness and death from common infections was down to improvements in public health, not antimicrobials. A good example of this is tuberculosis. Look at the graph below showing the mortality rate from TB in the 20th Century. Mortality came crashing down (with a couple of noticeable blips during wartime) during the first half of the century, and even though Streptomycin, the first drug active against tuberculosis, was discovered by Selman Waksman in the late 1940s, it didn’t become routinely available until the 1950s. By that stage the mortality from TB had already reduced dramatically, and all of this was due to improved public health.

The No. 1 threat from antimicrobial resistance - surgery

For me the number 1 threat from antimicrobial resistance is surgery… even though the Royal College of Surgeons refused to review our book “Microbiology Nuts and Bolts” when it was first published because “it didn’t affect them”… they are simply wrong.

Every time a surgeon cuts into a non-sterile body site such as the gastrointestinal, urogenital or respiratory tracts, antimicrobial prophylaxis is given to prevent any serious infections from developing. If a surgeon is putting in any prosthetic material such as a prosthetic joint, heart valve or even a device like a pacemaker, antimicrobial prophylaxis is given to prevent the prosthesis getting infected. Also, there will be no operations on sites where infection might be unlikely, but the consequences would be devastating such as the brain e.g. removing benign tumours, repairing aneurysms, or putting in ventriculoperitoneal shunts.

If there are no antimicrobials left, then there will be no surgery on non-sterile sites. There will be no surgery to implant prosthetic material. There will be no neurosurgery.

Antimicrobial resistance will pretty much wipe out the surgical disciplines, leaving behind a few brave souls willing to risk everything doing painstakingly slow operations to try and prevent any risk of infection, and only when there is absolutely no alternative. Discomfort, disabilities, deformities and deaths will be common.

The No. 2 threat from antimicrobial resistance - cancer

I think the number 2 threat from antimicrobial resistance is cancer. There are essentially two ways to treat cancer, cut out the tumour or kill it with chemotherapy.

We’ve already seen that antimicrobial resistance will prevent many surgical operations to remove tumours, but it will also affect the type of chemotherapy that can be given.

Most chemotherapy aims to selectively kill cancer cells, but the selectivity is often only partial. Many other cells are also killed as innocent bystanders, and the rapidly dividing cells, such as those that make up the immune system, are particularly prone to being affected by chemotherapy.

Once the immune system has been “knocked down” the patient is at risk of infection, both with common virulent microorganisms and also less virulent opportunistic microorganisms. In this situation antimicrobials are key because the patients’ own immune system is not able to fight the infection. In these cases even common infections that don’t normally cause deaths can be lethal.

If we don’t have any effective antimicrobials due to resistance, then we won’t be able to operate to remove cancers and we won’t be able to give chemotherapy because the subsequent infections will kill the patient.

We also give antimicrobial prophylaxis to patients being treated for cancer to try and prevent infections occurring but, you’ve guessed it, these won’t be able to be given as they will not be effective; antimicrobial prophylaxis just won’t work.

The net result of this will be that people will die from currently treatable cancers and the mortality from cancer will shoot up. It won’t necessarily be the cancer itself causing the problem but the infections.

The No. 3 threat from antimicrobial resistance – empirical treatments

The number 3 threat from antimicrobial resistance is empirical treatment of infections, or rather the failure of empirical treatment of infections.

If a patient has an infection the doctor looking after them usually starts what is known as empirical treatment; the best “educated” guess at what should work to treat the patient with their group of similar symptoms or disease. The doctor doesn’t know the exact cause, so they look at a guideline that tells them what to start to cover the most common causes of that type of infection. In the UK these guidelines are often written by Microbiologists, and they are based on the common causes, possible adverse effects of the treatment options (such as Clostridium difficile associated disease) and the local and national antimicrobial resistance rates (it might surprise you that we don’t just “make them up”!). If there is a lot of resistance to antimicrobials, then the empirical treatment needs to change.

As antimicrobial resistance increases, the available pool of antimicrobials reduce… currently the pool is getting shallower as drug companies are no longer making new antimicrobials. Eventually the pool will be empty and there will be no empirical antimicrobial options left.

So, the patient may have an otherwise treatable cause of their septic shock, such as a urinary tract infection or cholangitis, yet they will die because there were no effective antimicrobials available because of resistance.

So, there you have it. The Nuts & Bolts doom and gloom guide to the end of the antibiotic era… cheerful huh?! Well, looking on the bright side… if there are no antimicrobials left there will probably be no real need for Microbiologists and I can retire… just a thought… 😊

PS This retirement plan has not been approved by my financial advisor!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed