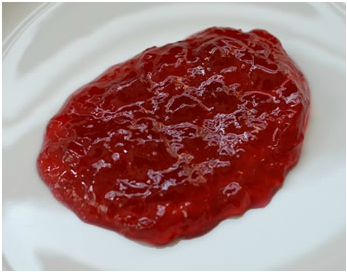

Further questioning revealed that he smoked about 40 cigarettes a day and drunk over 40 units of alcohol a week. He had not travelled recently and had no occupational risk factors for specific causes of pneumonia (e.g. plumber or heating engineer and Legionella pneumophila). Specifically I asked whether he was coughing up sputum that looked like “red currant jelly”. “It’s odd that you should ask that”, replied the doctor on the phone, “but yes, that’s exactly what he is coughing up”.

The patient was started on IV Meropenem and IV Clarithromycin. This is not the normal treatment of community acquired pneumonia (CAP) but I wanted to make sure that there was good cover for some of the more unusual bacterial causes, and given how unwell he was the initial treatment had to be effective (remember, for every hour a septic patient is not adequately treated the mortality increases by 7%).

That afternoon the patient’s blood cultures grew a Gram-negative bacillus which was identified as Klebsiella pneumoniae, and the diagnosis of Friedlander’s pneumonia was proven.

Friedlander’s pneumonia is a severe form of pneumonia caused by the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae. It tends to occur in patients who smoke and those who drink too much alcohol. The mortality is very high, ranging from 50-100% depending on underlying conditions such as alcoholism and whether the patient receives adequate antibiotic treatment and supportive care quickly.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is not a common cause of community acquired pneumonia, but when it does occur it is particularly severe. Patients are septic and usually require critical care support. There is a lot of lung damage, which results in them coughing up necrotic lung tissue and blood, the so called “red currant jelly” sputum. Many patients go on to develop abscesses in their lungs and require radiological or surgical drainage of these abscesses as well as prolonged courses of antibiotics.

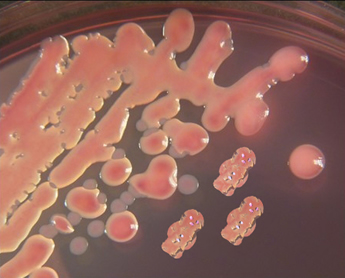

Klebsiella pneumoniae is part of the group of Gram-negative bacilli called the Enterobacteriaceae, which are part of the normal flora of the gastrointestinal tract. It is a facultative anaerobe growing both aerobically and anaerobically. K. pneumoniae can be distinguished from the other common lactose-fermenting Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli) by its ability to use citrate as a source of carbon. It is often very mucoid when grown on blood agar in the laboratory due to the production of lots of bacterial capsule; often resembling half-chewed red jelly babies! Nowadays laboratories tend to use faster methods to distinguish the different Enterobacteriaceae e.g. MaldiTOF.

Carl Friedlander was a German pathologist and one of the early microbiologists who in 1882 described the bacteria causing severe pneumonia. He observed a Gram-negative bacillus in the airways of patients dying from pneumonia, which turned out to be Klebsiella pneumoniae. Although this bacterium was named after Edwin Klebs (an earlier pathologist who inspired the likes of Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur to study microbiology) it is often referred to as Friedlander’s bacillus because of the clinical condition it caused.

The clinical picture described by Friedlander back in 1882 when he made his observations was of severe pneumonia, with patients coughing up necrotic lung tissue, which inevitably resulted in death. This clinical condition became known as Friedlander’s pneumonia.

Antibiotic resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae

All Klebsiella pneumoniae produce a beta-lactamase giving inherent resistance to Amoxicillin and Ampicillin. More recently, strains of K. pneumoniae are being isolated from patients which are resistant to lots of different antibiotics. In particular, K. pneumoniae has acquired the genes for AmpC, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and more recently carbapenemases.

Carbapenemases cause resistance to all of the currently available beta-lactam antibiotics including the carbapenems e.g. Meropenem, Imipenem and Ertapenem, and are often associated with other resistance mechanisms to alternative antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides. The most common carbapenemase in K. pneumoniae is actually helpfully called the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC). KPC was originally a problem in North America, but from there it has now spread globally. By 2013, 1% of all K. pneumoniae isolated from patients’ blood cultures in the UK had the KPC enzyme. This may not sound like a lot, but this had occurred over only three years and the situation is likely to get worse.

The treatment of carbapenemase producing K. pneumoniae is with a combination of Colistin PLUS either Tigecycline OR Amikacin OR Meropenem (even though it tests resistant in a laboratory combining Meropenem with Colistin is often effective in patients). Not only are these treatments IV but they are also potentially nephrotoxic, especially the combination of Colistin PLUS Amikacin.

Fortunately for this patient he was diagnosed and started on effective treatment very quickly. The K. pneumoniae was only resistant to Amoxicillin and Ampicillin and his treatment was narrowed down to Co-amoxiclav. He spent about 2 weeks ventilated on ICU, but slowly improved. He did not develop abscesses and eventually made a good recovery but he may well have ongoing reduced lung function as a result of the damage the infection has caused.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed