Previously I wrote a couple of blogs about Poldark’s Putrid Throat and Poldark’s Putrid Throat Revisited. This time I am going to tackle a new diagnosis from the latest series of the hit BBC drama. If you haven’t watched series 4 yet and don’t want to know what happens then best not to read any further… there will be spoilers… you have been warned! ***WARNING – SPOILERS***

Okay, so the big scandal at the end of series 3 was the illicit romance between Demelza Poldark and Lieutenant Hugh Armitage. Lt. Armitage was a companion of Dr Dwight Enys during his incarceration in a French prison after their ship was captured by the French. Dr Enys and Lt. Armitage were eventually rescued in a daring plan by Ross Poldark but it quickly became apparent that Lt. Armitage was not a well man.

To cut a long and somewhat drawn out story short, towards the beginning of series 4, Lt. Armitage succumbs and dies from what is termed a “Brain Fever” leaving Demelza devastated and Ross still reeling with jealousy that he had a competitor for Demelza’s affections. But, enough of the soap opera (which in my opinion the gritty Poldark series has become), this is a microbiology blog, so what in the 19th Century might have been the cause of the “Brain Fever” which killed Lt. Armitage?

I have looked in a number of old medical books (I really love antique medical books!) and can find no reference to the diagnosis, except some vague notes towards psychological diseases, but I rather think from seeing Lt. Armitage’s presentation, “Brain Fever” probably had a more organic cause.

So in Part 1 of this blog, I’m going to try and work out what I think the cause of “Brain Fever” was. The place to start is with the history and examination and then I need to formulate and explore a differential diagnosis. In Part 2, next week, I will think about how this would be managed in a modern hospital.

History of presenting complaint

The principal symptoms are headache and fever. These began during our patient’s stay in prison in France following the sinking of the ship he had been serving on. The conditions of the prison were awful; we can assume that hygiene was a major problem, that there would be open sewerage and lots of rats, fleas and lice.

Following our patient’s escape from prison the symptoms continued over the following months in a chronic relapsing manner. Periods of feeling okay were broken by periods of severe headaches and fever.

A systems review reveals generalised feelings of tiredness, weakness, myalgia, weight loss, loss of appetite and progressive loss of vision. On many occasions our patient has to take to his bed having no energy at all.

On examination there is generalised muscle weakness but no localising neurological symptoms, which if present would indicate a specific area of the brain was affected.

So we have our list of symptoms and signs, now we need to start exploring the differential diagnosis of headache PLUS fever.

Differential diagnosis of headache PLUS fever

The main differential diagnoses for headache and fever include:

- Intracranial infection – meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess, subdural empyema (pus in the CSF)

- Systemic infection – bacterial or viral, HIV/AIDS (although HIV/AIDS is not thought to have been around in the 19th Century!)

- Non-infectious – familial hemiplegic migraine, pituitary apoplexy, subarachnoid haemorrhage, rhinosinusitis, intracranial malignancy

So let’s start pulling this differential apart.

I’m going to start with the non-infectious causes first so I can get them out of the way (this is a microbiology blog after all!)

Familial hemiplegic migraine is an unusual form of migraine in which the patient experiences localising neurological signs along with the headaches and fever. It is a very rare cause of death, and only when associated with seizures or coma, and therefore it is very unlikely to be the cause of death in our patient.

Pituitary apoplexy describes a condition where there is acute haemorrhage into the pituitary gland. The patient has a sudden onset of headache and visual loss as blood presses on the optic nerves, but it isn’t a relapsing chronic condition so this is not the cause in our patient either. For the same reason a subarachnoid haemorrhage is not the cause as this again doesn’t give a chronic relapsing pattern.

Rhinosinusitis is a very slight possibility, in that, if it is very severe and the sinuses can’t discharge into the nasal cavity then there can be extension from the sinuses though the bones of the skull and into the brain causing an abscess. Our patient doesn’t describe sinus pain or purulent discharge from the sinuses so I am going to cross this off the list for now.

An intracerebral malignancy is also a possibility as this could give the relapsing chronic headaches and fevers. Brain tumours are associated with oedema (swelling) which can come and go. It is often the oedema that causes the headache and therefore if the oedema comes and goes so does the headache. The classic description of a brain tumour headache is one that wakes the patient in the morning and then fades after they get up. This is because the oedema gets worse under gravity when lying down and then improves after getting up because gravity pulls the fluid out of the brain again. This would probably stay as part of the differential diagnosis normally but I’m going to cross it off because whatever our patient has was “caught in prison” and brain tumours are not contagious.

Moving on to the microbiology I think a systemic infection is also unlikely. None of these would explain the chronic relapsing nature of the disease or the progressive visual loss. Whatever is going on is likely to be primarily located in our patients head.

So now we get to the intracranial infections. A subdural empyema is a collection of pus that usually forms after meningitis. In order to develop a subdural empyema you have to have survived the acute bacterial meningitis; in an era without antibiotics this is not going to have happened. So this diagnosis is discounted too.

A brain abscess is possible but the lack of localising neurological signs makes it unlikely, especially as it would have got bigger and bigger over time and would eventually have pressed on something that would have given abnormal neurology.

Acute encephalitis is also unlikely. If the patient survived this then there would be no reason to expect a relapsing history.

This leaves us with meningitis. Now this is not going to be the acute meningitis we predominantly see in the UK with bacteria such as Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae, or viruses such as the enteroviruses. This is chronic meningitis, and the causes are very different.

Chronic meningitis could explain all of our patient’s symptoms and signs and so this is our working diagnosis. Now we can work out the cause.

Chronic meningitis

There are a host of different causes of chronic meningitis, some of which are non-infectious. However our patient acquired his meningitis in prison and this is much more in keeping with an infectious aetiology. The infectious causes of chronic meningitis include:

- Bacteria – tuberculosis, Lyme disease, syphilis, leptospirosis, brucellosis, tularaemia, actinomycosis, listeriosis, ehrlichiosis, nocardiosis, Whipple’s disease

- Viral – HIV, CMV, EBV, HTLV, Enterovirus, HSV, VZV

- Fungal – cryptococcosis, sporotrichosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidiomycosis

- Parasitic – cysticercosis, angiostrongylosis, schistosomiasis, toxoplasmosis, acanthamoebiasis

Okay, so there are some horrendous names in there; I have always maintained that microbiology is as much a language as a science. I’m NOT going to go through every microorganism in detail, I will just give the reasons why I would exclude them… maybe future blogs will tackle the ones I’ve not covered before.

I am rejecting the bacterial causes for their own specific reasons, and also because they all tend to be progressive with continuous worsening symptoms rather than relapsing. Tuberculosis is unlikely as in this era our patient is very likely to have had tuberculosis as a child and therefore to develop meningitis later in life would be unusual. Lyme disease, brucellosis, tularaemia and ehrlichiosis can all be rejected because our patient wouldn’t have come in to contact with the animals or ticks that spread these diseases (the tick Ixodes spp. in Lyme, cattle, sheep and goats in brucellosis, bites of arthropods like ticks and mosquitoes in tularaemia and ticks in ehrlichiosis).

Rats could easily have spread leptospirosis but the lack of renal or liver symptoms or signs make this unlikely. I am also going to assume he didn’t have the opportunity to catch syphilis in prison (as it’s a sexually transmitted disease!) and that he wasn’t given any unpasteurised French cheeses in order to catch listeriosis. The actinomycosis and nocardiosis I am going to reject because he is not specifically immunocompromised nor did he show any dental problems we are aware of (Demelza certainly didn’t complain he had bad breath!).

I am rejecting the viruses because they tend not to give relapsing symptoms in chronic meningitis. It is also unlikely that he would have acquired them in prison as most require some form of exchange of body fluid.

Next we come to the fungi. These could explain the relapsing chronic meningitis but our patient is not immunosuppressed enough to develop something like cryptococcosis or sporotrichosis and he will not have been exposed to the other fungi (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis or coccidiomycosis) as they are not endemic in Europe.

So this leaves us with only the parasites, so let’s look at these in turn.

Cysticercosis is an infection with the pork tapeworm. Infection is usually asymptomatic and I’m sure our patient was not given something as good as a hog roast sandwich to eat, even one riddled with tape worm cysts, so this is off the differential too.

Angiostrongylosis is caused by the rat lung-worm and is usually self-limiting, so off the differential it goes.

Schistosomiasis is an infection with either intestinal or bladder shistosomes. In order to cause chronic meningitis the patient is usually immunosuppressed and would have to have gone to Africa or Asia to catch the organism, so I can reject yet another microorganism.

Toxoplasmosis is a possibility given the exposure to rats and the visual disturbance. It might also have promoted the subsequent risky behaviour with Demelza once our patient had escaped from prison (but that’s a topic for another blog!) However toxoplasmosis is rarely fatal and so I have to cross this off our differential as well.

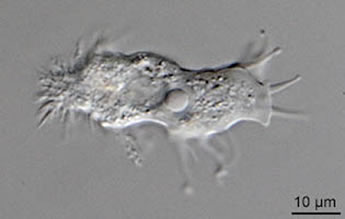

So we are left with acanthamoebiasis; could this explain our patient’s symptoms and signs?

Acanthamoeba spp. are found in soil and water especially brackish water and sewerage (like in a French port prison) but also in the modern era in humidifiers, heating systems and contact lens fluids. Be warned “Brain Fever” could still present in modern times!

So there we have it, having excluded everything else the most likely diagnosis of Poldark’s “Brain Fever” is granulomatous amoebic meningoencephalitis caused by Acanthamoeba spp. It fits clinically and it fits epidemiologically.

In the next blog I will tell you more about this condition, and what Dr Enys could have done about it had he been working in a modern health care setting rather than 19th Century Cornwall.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed