Essentially this is a case of pyrexia of unknown origin or PUO. What is PUO and what should you do about it?

Pyrexia of unknown origin has a strict definition:

Classic |

A temperature >38°C for >3 weeks PLUS >2 visits to hospital OR >3 days of investigation in hospital |

What are the common causes of PUO?

In the past, infection was the most common cause of PUO but in the era of modern medicine that has changed. Two things have changed the balance of causes; people living longer and better diagnostic tests.

Microbiology investigations have improved considerably in recent years, with better bacterial culture systems, including for tuberculosis, as well as serological and molecular tests for microorganisms. As a result the number of undiagnosed infections has reduced. In addition, people are living longer and therefore the incidence of diseases like cancer, connective tissue diseases and autoimmune conditions are increasing as these are more common the older you get. Cancer diagnostics however are also improving so diagnosis is much faster and therefore cancer forms less of the PUO group than it did before.

The most common causes of PUO include:

- Infection (11-19%)

- Infective endocarditis

- Tuberculosis

- Urinary tract infection

- Malignancy (7-20%)

- Connective tissue disorder (22-33%)

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Temporal arteritis

- Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Other diagnosis (4-10%)

- Undiagnosed (33-51%)

Initial management of the patient

It is critical that you don’t empirically start antibiotics unless the patient is septic or very unwell. Antibiotics will prevent the growth of bacteria and therefore make diagnosing the cause of the patient’s pyrexia almost impossible. For example, commonly used antibiotics like Co-amoxiclav, Gentamicin and Ciprofloxacin all have activity against tuberculosis (in fact they are often part of the multidrug resistant tuberculosis regimens) and will stop Mycobacterium tuberculosis growing in cultures even though these antibiotics on their own won’t successfully treat the infection… they just make it impossible to diagnose TB.

If you must start antibiotics because the patient is very unwell then treat for sepsis or the most likely alternative diagnoses.

Remember, just because you haven’t started any antibiotics doesn’t mean you shouldn’t treat the patient at all. Good supportive care must be given. If necessary give antipyretics to control the fever and make the patient feel better, consider antiemetics if the patient is vomiting, give anti-inflammatories and pain relief if necessary and IV fluids if they are dehydrated. All of this can be done while you are trying to work out what the underlying diagnosis is.

How do you investigate PUO?

Keep it simple… I repeat keep it simple!

It is very tempting to rush in and test for every possible cause of PUO that you can possibly think of, and if you have access to Google it is easy to find hundreds of conditions the patient just might possibly have… don’t do it!

Start by taking a detailed history of the patient’s illness. In addition to exploring the patient’s symptoms other questions that can help include:

- When did they first become unwell? – is this an acute infection over a few days or a more chronic infection like TB or endocarditis or even cancer?

- Have they had a similar illness in the past? – a recurrent problem is more likely to be a connective tissue disorder or autoimmune problem

- Have they had contact with anyone else who is unwell? – many infections are spread person-to-person and if someone else is ill they may have the same thing

- Has anyone in their family ever had a similar illness? – some connective tissue disorders or autoimmune problems are familial

- What do they do for a job? – some jobs increase the risk of infections e.g. a plumber might be at higher risk of legionellosis, a vet from zoonotic infections from animals

- Do they have any particular hobbies or past times? – environmental exposure to infections can occur e.g. canoeists are at increased risk of leptospirosis, a bacterial infection transmitted by rats

- Have they got any pets? – zoonotic infections such as Salmonella from reptiles, rat bite fever from rats, Capnocytophaga from dogs

- Have they travelled recently or in the past? – could this be an unusual tropical or foreign infection e.g. malaria, brucella, Q Fever

- Have they had any operations or do they have any prosthetic material in their bodies? – infective endocarditis is more common on prosthetic heart valves

- Have they noticed any odd lumps or bumps? - connective tissue disorders often present with soft tissue swellings, lymphoma can present with abnormally large lymph glands

- Have they got any swollen joints? - connective tissue disorders often present with swollen joints

- Have they got any pain anywhere? – this might help localise the problem and point to where the investigations should focus, e.g. pain in the abdomen might direct imaging of the liver, urinary tract and bowel

Once you do have a good history you can formulate a differential diagnosis of what you think could be wrong with the patient and then you can work through the list of diagnoses from life-threatening and common to the more rare diseases.

When sending tests, be systematic. Do not send every test under the sun. Keep in mind that “common things are common” and even if the presentation of the disease is a bit “unusual” it is still more likely to be a “common disease presenting in an uncommon way” rather than a rare disease.

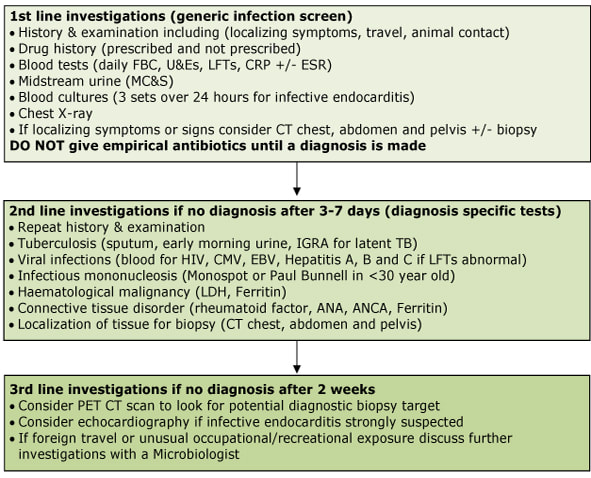

My strategy for investigating a PUO is as follows:

And if you don’t find a cause and the patient gets better on their own without anything other than supportive treatment then that is also good. It might be academically frustrating but who cares, they’re better and that is all that really matters!

So our patient wasn’t started on antibiotics initially. A thorough history was taken and a comprehensive examination was performed. There was nothing to find initially and so we waited to see if they would improve with good supportive care with fluids and antipyretics.

The following day she hadn’t improved and in fact the patient was a bit worse, so further investigations were arranged. She had a full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests and a lipase in case this was pancreatitis. A urine sample was taken to look for a UTI. All of the tests came back negative.

As the patient still wasn’t improving, and was in fact worsening, we repeated some of the initial blood tests and urine screen to see if there had been any change, and moved on to second line tests including an ultrasound scan of her abdomen, as she was slightly tender around her kidneys but again these investigations didn’t identify a cause. Lack of nutrition was a concern as it was over a week since she had eaten properly, so a nasogastric tube was inserted and nutrition administered.

Two days passed and the patient had still shown no signs of improvement, no test results confirmed a diagnosis and she was getting worse so it was decided to start antibiotics empirically “just in case” this was an infection and she was given Co-amoxiclav. She was also started on a regular anti-pyretic and anti-inflammatory, an antiemetic and 3 hourly fluids. Blood tests were taken to look for infectious causes.

Over the next few days the patient started to improve a little and is now more like her normal self… she chirrups when we walk into the room and purrs when she is cuddled and made a fuss of. She has started to eat “Dreamies” treats and a bit of wet food and now growls and swishes her tail when we give her her food via her oesophagostmy (much more tortoiseshell behaviour!) … oh, did I forget to mention, the patient with the PUO is our cat Granola!

- Don’t start unnecessary antibiotics

- Take a good history and perform a good clinical examination

- Be systematic when investigating and remember “common things are common”

- Provide good supportive care whilst looking for the cause

- If the patient gets better without knowing the cause then that is a good thing

And one last thing that we learned with Granola… if you have a cat that won’t eat then don’t delay in getting them to a vet. Cats cannot fast, if they don’t eat they start to mobilise their fat stores like humans but unlike us they don’t use them efficiently for energy and instead flood their livers with the fat which can be fatal… a condition called hepatic lipidosis… they must feed even if that means feeding them through a tube until they get better…. Oh look at the time, time for another feed! …although we are now on a reducing amount with plans to remove the oesophagostmy next week.

Thank you all for your supportive comments and especially thanks to our fantastic vet team!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed