Having explained that the doctor really should have gone to his own seniors first, as they would have probably known what this was, the Microbiologist reassured the doctor that this was a common fungal infection of the scalp (tinea capitis) but it also sounded like the boy had a complication called a kerion. The Microbiologist advised on what samples to take and how to treat the infection. He finished by telling the doctor to “keep calm and kerion”… but the joke was lost on the stressed doctor…

What is tinea capitis?

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp which causes scaling of the skin and loss of hair (alopecia). It is commonly caused by dermatophyte fungi. These fungi can be acquired from people, soil and also animals. Tinea capitis is very common and primarily affects children. It can be found throughout the World.

What are the dermatophytes?

Dermatophytes are filamentous fungi that like to infect tissue containing keratin, a structural protein found in skin, hair and nails. Dermatophyte means a “plant-like organism on the skin”. The main species of dermatophytes causing tinea capitis are Trichophyton spp. and Microsporum spp. These can then be divided further depending on where they are acquired from. Some of the names can tell you random facts about the fungus but others are even less useful!

From humans

T. tonsurans – the medieval practice of shaving a monks head was known as a tonsure

T. mentagrophytes var. interdigitale – interdigitale means between fingers, this can also cause skin and nail infections

T. violaceum – has a purple colour (viola flowers are purple) on its underside when growing in the laboratory

T. soudanense – Soudan was the French name for Sudan in Africa, presumably where this was first isolated

T. schoenleinii – named after the German naturalist Johann Lukas Schönlein

M. audouinii – named after the French naturalist Jean Victor Audouin

From animals

M. canis – canis relates to dogs

T. verrucosum – verrucosum is latin for rugged lesions

T. equinum –equinum relates to horses

M. nanum – not sure about this one, nanum can be used to mean small so maybe this has something to do with small animals?!

From soil

M. gypseum – gypsum is a soft mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate

M. fulvum – fulvus is a red colouration; minerals are often described in this way if they have a red pigment

At the end of the day it doesn’t really matter what the causative fungus is, the important point is that the patient has tinea capitis whatever the species.

How does tinea capitis present?

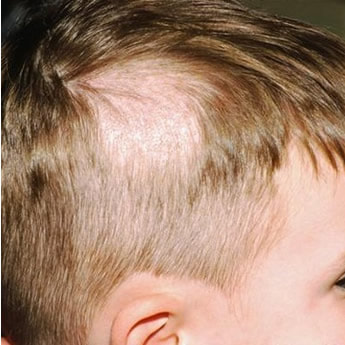

Some people can carry dermatophytes asymptomatically but the majority of tinea capitis presents in one of five ways.

- Scaly patches with alopecia – the patches are usually a few centimetres in diameter but they can get larger over weeks to months

- Alopecia with black dots – the black dots are hairs that have broken off as they leave the hair follicle because the hair shaft has become weak as a result of infection

- Widespread skin scaling with little hair loss – which may mimic other forms of skin disease such as seborrheic dermatitis

- Favus – mainly caused by T. schoenleinii, erythema occurs around the hair follicles leading to cup-shaped yellow crusts called scutula which eventually join together to cause severe alopecia and permanent scarring

- Kerion – a severe form of tinea capitis presenting with severe pain and tenderness, caused by an intense immune response to the fungal infection, which leads to thick crusting of the skin and the formation of pustules which might start to discharge. These pustules may or may not be secondarily infected with bacteria; the only way to find out is to send either pus or a swab to a microbiology laboratory for culture.

How is tinea capitis diagnosed?

Most tinea capitis is diagnosed clinically with the typical appearance of scaling and alopecia in a child, however if there is any doubt then samples of skin or hair can be sent to the microbiology laboratory. The main scenario when the diagnosis might need to be confirmed by the laboratory is in adults where the diagnosis is uncommon and might suggest an underlying immunity problem. If you do send hair to the laboratory for investigation it is important to make sure the follicle is intact i.e. the hair must be pulled out, not cut, as the fungus primarily infects the hair follicle itself.

In the laboratory the skin or hair is both examined by microscopy and culture. Microscopy is performed after adding potassium hydroxide to the hair follicles or skin in order to dissolve the keratin allowing the fungal hyphae to be seen more easily. Culture of skin or hair can also be done but the results can take several weeks to be positive as these fungi are very slow growing.

Treatment should be started as soon as there is a typical clinical history, backed up by microscopy if necessary. Culture is just the icing on the cake and shows the likely causative organism and where it might have come from e.g. another person or animal might also need treating.

How is tinea capitis treated?

Tinea capitis is treated with oral antifungals; topical agents do not work. The dose is dependent on the age and size of the patient, see the BNF for more details.

1st Line |

PO Griseofulvin |

2nd line (if 1st line contraindicated) |

PO Terbinafine |

Fluconazole and Itraconazole can also be used to treat tinea capitis but the evidence is much more limited so they should be reserved for patients who are unable to take Griseofulvin or Terbinafine.

Kerions are treated in the same way as other forms of tinea capitis. If there is evidence of a secondary bacterial infection then antibiotics targeted against the causative bacteria should be given. As with other types of skin and soft tissue infection, this would usually be Flucloxacillin which is active against both Staphylococcus aureus and the beta-haemolytic streptococci.

Asymptomatic household contacts of a patient with tinea capitis should also be treated with an antifungal shampoo in case they are carriers of the fungus. Contacts should also avoid sharing towels, hair care tools (e.g. brushes and combs) and head wear such as hats to try and prevent spread of the infection. Any possible animals that might be infected or carriers might need treating by a veterinary surgeon.

With treatment tinea capitis usually resolves completely with no scarring or permanent hair loss, however permanent hair loss is more likely to occur with kerions or favus.

So a sample of the little boy’s hair was sent to the microbiology laboratory and he was discharged on a course of Griseofulvin. The microscopy confirmed tinea capitis and the culture eventually grew M. canis. The family was advised by their GP to ensure the family’s pet dog was examined by a vet. The dog was also suffering from a fungal skin infection; the little boy and the dog both took their shampooing badly but both patients (boy and dog) made a full recovery.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed