It turned out that the patient was in her mid-thirties and a contact lens wearer who had presented to the eye casualty unit with a painful red eye which had been diagnosed clinically as keratitis. The Ophthalmologist had taken a sample and started treatment for bacterial keratitis, the most common cause, as an outpatient with topical Levofloxacin 0.5% eye drops. The Ophthalmologist admitted that they weren’t confident that the patient was that careful with the sterility of their contact lens solutions.

The Microbiologist told the Ophthalmologist that a Fusarium species had been isolated confirming the diagnosis of fusarium keratitis so the patient was recalled for alternative treatment targeted at the fungal cause rather than the previously suspected bacterial one.

What is keratitis?

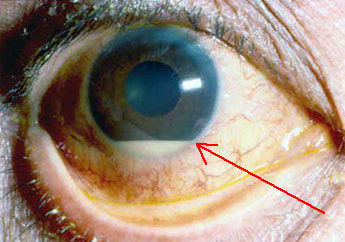

Keratitis is inflammation of the cornea of the eye. It can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. It typically presents with a painful red eye, increased sensitivity to light, and excessive production of tears. As the infection progresses a hypopyon may develop (pus in the anterior chamber of the eye; gravity causes the pus to form a level line). Eventually the cornea may perforate, become scarred and cloudy, and the patient may become blind in that eye.

What is fusarium?

Fusarium is the name given to a group of fungi that can cause infections in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. They are found all over the World in soil and water. There are over 100 different fusarium fungi but most infections in humans are caused by Fusarium solani (>50%), Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium verticillioides and Fusarium proliferatum. Almost all fusarium keratitis is caused by F. solani.

Fusarium spp. are easily grown in the microbiology laboratory; in fact they are a bit too easy to grow. They will grow rapidly on any agar that doesn’t contain the chemical cyclohexamide which means that if a plate is contaminated with fusarium spores it will grow on the plate and the biomedical scientist will have the problem of trying to work out if the fungus was genuinely in the patients sample or whether it is actually a contaminant. This can be tricky, but there are two tell-tale signs 1) if the fungi looks to be growing at the edge of the agar plate where it might have blown in or 2) is growing outside the area of the plate that was inoculated with sample, both are likely to be a contaminant.

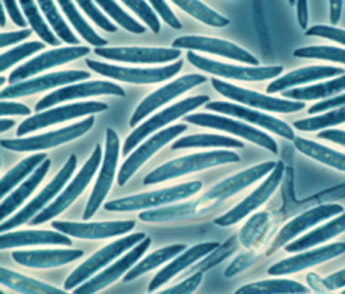

Because there are so many different species of fusarium the colonial appearance on agar is not always able to differentiate Fusarium spp. from other moulds. Also, Fusarium spp. appear similar to Aspergillus spp. on microscopy because they produce septate hyphae that branch at an acute angle. The main method of identification, as for many fungi, is to look at the macroconidia (a large spore like structure on a fungus) which has a distinctive appearance for the Fusarium spp. and looks a bit like a banana (see picture). There are also molecular methods for identifying Fusarium spp. and apparently MALDI-TOF is also able to identify these fungi.

Fusarium normally gets into the eye to cause keratitis in one of two ways:

- Poor hygiene in contact lens wearers who contaminate their contact lens solution with fusarium which then infects the eye

- Traumatic introduction of soil or other debris into the eye

Many Fusarium spp. are able to produce toxins which break down proteins and collagen as well as suppress the patient’s immune system which allows the fungus to establish an infection once it has been introduced into the body.

How is fusarium keratitis treated?

Treatment of fusarium keratitis should be guided by an experience Ophthalmologist. Fusarium keratitis is difficult to treat as the fungi are resistant to the echinocandin antifungals and have relatively high minimum inhibitory concentrations to azoles and Amphotericin B. Added to this, antifungals do not get into the eye well from the systemic circulation. The principals of treatment are to use a topical antifungal, sometimes with a systemic antifungal added in.

In the UK topical Voriconazole is usually the mainstay of treatment although topical Amphotericin B has also been used. If the infection is very severe the patient may also be given systemic Voriconazole as well to try and boost drug levels even higher. There is no hard and fast rule for how long to treat these patients; treatment is continued until the cornea has healed which can take many months.

If the infection does not respond to treatment and the cornea does not heal then the final ultimate treatment is to remove the cornea and perform a cornea transplant but this is obviously a major undertaking so antifungals are always tried first.

Our patient came back to the eye unit for further evaluation and to change treatment to topical Voriconazole. They were given strict advice about how to care for their contact lenses, although they were not allowed to use contact lenses whilst the infection was still ongoing. They were also told to throw away their old equipment and solutions as these would be an ongoing source of infection. Fortunately after several months the patient did make a full recovery, but they never went back to using contact lenses… they started to think about having laser eye surgery instead… another shudder, there is no way I’m giving up my glasses!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed