Doctors around the country quickly expressed their concern not over the failings in care but over the GMCs decision to go against the recommendation of the Medical tribunal, who suggested a 1 year suspension from practise. The GMC went to the High Court to have Dr Bawa-Garba struck off. In the pit of my stomach being struck off seemed excessive; Dr Bawa-Garba appeared to have been made a scape-goat for “all-too-regular” events such as returning from leave, being short staffed, chaotic or dysfunctional work environments and policies, lack of senior cover, problems with computer systems, and making common mistakes. Sadly on this occasion the combined events had dreadful results. So why do we feel so affected, is it because we all see a bit of ourselves in Dr Bawa-Garba’s situation?

Can I evaluate this incident? What advice would I give to other healthcare staff to try and protect them from making the same mistakes?

We are all human

Doctors, like all healthcare staff, are human and therefore we make mistakes. The problem is that when we make mistakes the consequences are often very bad; patients come to harm and even sometimes die. Mistakes can be limited by checking…for example when a patient goes for an operation checks are made: names are checked verbally and using the patient’s wrist band, drugs are checked by the anaesthetist and an assistant, the relevant body site is clearly marked before the patient is put to sleep, things are checked and checked again.

I personally feel it is okay to make mistakes with two caveats:

- You make the mistake for the right reasons – for example if a patient has right upper quadrant pain, a fever and slightly abnormal liver enzymes you would think they might have cholecystitis, cholangitis or hepatitis… and investigate accordingly. However if they turn out to have a malrotated bowel (a very rare congenital anomaly where the small intestine is predominantly found on the right side of the abdomen) and have in fact got appendicitis then it is okay to have “missed it”, you were right to consider the much more common causes of right upper quadrant pain

- You learn from your mistakes so that you don’t make the same mistake twice – continuing to make the same mistake suggests you are unwilling to learn, change your practice or you fail to accept that you made the mistake in the first place. All are dangerous as they suggest you will make the same mistake again and again.

Failing to diagnose sepsis is a mistake. But it is a common mistake that occurs daily in the NHS, which is why the Surviving Sepsis campaign was initiated and continues to be so important. The lactate of 11 mmol/L in Jack’s case is a strong indicator for sepsis and alarm bells should have rung but they didn’t. Blood lactate is a measure of how much anaerobic metabolism is going on in tissue. If there is inadequate blood flow to tissue, metabolism becomes anaerobic and lactate goes up and is a marker of sepsis and septic shock. A lactate above 2mmol/L is abnormal and above 4mmol/L is alarming… so 11mmol/L should be downright frightening.

To prosecute a single doctor for negligent manslaughter for missing sepsis, as in the case of Dr Bawa-Garba, does seem very unfair. There may be more to this part of the story which we are unaware of, but if not it is a very tough sanction. In addition Dr Bawa-Garba now recognises she failed to recognise sepsis and has learnt from it. Can you recognise sepsis?

Prescriptions and Drug Charts

I have concerns that Jack was given a medication that hadn’t been prescribed on his drug chart. It is reported that a Nurse took a “verbal instruction” from a Junior Doctor (other than Dr Bawa-Garba) that as Jack’s normal ACE inhibitor wasn’t prescribed on the drug chart the staff could not administer it, but his mother could give it to him as normal. Now, Dr Bawa-Garba had apparently made a decision to deliberately withhold the ACE inhibitor because Jack was hypotensive on admission, had the high lactate and had abnormal renal function. This was the correct decision because in this situation an ACE inhibitor is contraindicated. So why did someone else “say” it was okay to give it? Was Dr Bawa-Garba’s decision to withhold it documented and communicated to the Nurses and parents? We don’t know for certain, but in my opinion no drug should be given in hospital without being prescribed on a drug chart, not even herbal remedies or over the counter drugs. Also if you withhold “normally prescribed” medication you must document why and communicate this to the patient/relatives.

Prescriptions exist for a reason, they can be checked. If a drug is prescribed for a patient in hospital, good practice dictates that the prescription will be checked by a pharmacist and then checked again by two nurses working together on the drug round before it is given to the patient. This means that for a patient to be given the wrong medication four people need to get it wrong; there are four opportunities to prevent the error. This wasn’t the case at the Leicester Royal Infirmary. The drug wasn’t prescribed, it wasn’t check by a pharmacist and the responsibility for administering the drug was handed over to the mother… the system failed because good practice wasn’t followed.

Drug interactions and contra-indications

Why does the giving of the “normally prescribed” ACE inhibitor matter? By the time this drug was given Jack was apparently sitting up in bed talking to his parents, drinking from a bottle and looking much brighter. However in renal failure, hypotension and poor tissue perfusion, an ACE inhibitor can send the patients potassium up very high (hyperkalaemia) and the consequence of this is that the patient’s heart will stop. The heart cells are suddenly no longer able to repolarise, they just stop beating and it is very hard to resuscitate these patients. I find it a bit strange that more hasn’t been made of this as a potential cause of Jack’s death. Checking for drug interactions and contra-indications is a necessary part of prescribing and can be vital as many drugs should not be used in conjunction or used when a new diagnosis presents.

The “known” diagnosis

Another concern I have is that having made a diagnosis of gastroenteritis Dr Bawa-Garba and the clinical team appear to have become “blinkered” by this “known” diagnosis. They appear to have failed to consider other diagnoses even when there was evidence that Jack didn’t just have gastroenteritis, as shown by the lactate result. In my experience this is usually because doctors don’t formulate a differential diagnosis; they decide on what is wrong and they continue to follow that diagnosis even though it may be wrong and the patient’s symptoms are explained by other conditions. See the previous differential diagnosis blog for more about this key skill of being a doctor.

New to position or returning from leave

I think it is very wrong to put someone “in charge” that is either new to the position or just come back from a long period of leave, Dr Bawa-Garba had only just returned from maternity leave. Returning from long periods of leave means not only will the doctors skills not be as sharp as before their leave, but it will take them time to get back into the “swing of things”. I know how I feel returning straight back on-duty after a short 2 week holiday…hundreds of e-mails, changes to policies, new staff faces, my coffee cup “stolen”, the canteen menu refreshed, and the blue corridor repainted red etc, etc! It can be disorientating. Likewise with “moving jobs”, this often involves moving hospital and therefore homes as well. It’s a scary time; you’ve just got familiar with what you are doing and then off you go again.

Most Junior Doctors can fit all of their worldly goods in their car so they can up and move between 6pm one day and 8am the next! It’s not just scary for them but for the rest of the healthcare staff who overnight lose the doctor’s they knew and trusted and gain a new set, who sometimes (justifiably) seem to flounder in their first week(s). The lack of slack in staffing rotas makes relying on this person “just-back” all too familiar and although it may be nice to have an extra pair of hands again we need to ensure these “fresh hands” are fully up-to-speed.

Senior Support

So where was the senior support for Dr Bawa-Garba? According to the reports the Consultant Paediatrician oncall that day was not actually in the hospital but giving lectures off site. To my mind that is wrong. If you are a front line clinician you should at least be close to the front line and by that I mean: on site, “reachable” or “covered” by someone equally senior. Additionally it is claimed that the Consultant chose not to review Jack despite being told he had had a lactate of 11mmol/L when he was admitted. That is also wrong…a lactate of 11mmol/L should be downright frightening even to a Consultant. The public information does not focus or give an explanation for this lack of senior support or review.

But did Dr Bawa-Garba document that she had told the Consultant and did she raise concerns about the lack of senior support?

If you haven’t written it down, you haven’t done it

This is an old saying in medicine which stems from how you provide a strong medicolegal defence of your actions. In a court, if you say you did something and you documented in the patient’s clinical notes that you did it, then it is very likely that you did it. This contemporaneous record also suggests you did it at the time you say you did. On the other hand if you haven’t written it down there is no proof you did it other than your word, which will not be treated with high regard as you have failed to follow professional guidelines for documenting things!

All written records should have a date, time, signature, printed name, grade of staff and contact number as well as a clear description of what you did or said. I give 2000-3000 episodes of telephone advice a year and I document those calls on the laboratory computer system so there is a record of what I said, when I said it and to whom. It may seem pedantic but am I really going to remember these conversations in 5 years’ time unless I have documented them. You might think I can rely on the other person writing the conversation in the patient’s notes; I can’t, so I take the responsibility myself.

Perhaps one of the problems for Dr Bawa-Garba is that although she says she did various things like she told the covering Consultant about Jack, maybe she hasn’t written any of this down so she has no proof that she did it and therefore any legal defence becomes very difficult.

If you have concerns make them heard

Incident reporting systems in hospitals exist for a reason and they can be your friend. They allow staff to raise concerns about patient safety issues, so that organisations can make changes before something larger happens. If managers ignore incident reports and then something goes wrong it is much easier to defend yourself because you have proof that it was escalated within the hospital. Use the reports carefully and not frivolously. If the incident reports are ignored and you still have concerns put these concerns in writing to your line manager or even their line manager. Most people working in the NHS want to do what is right, they just might not be aware of just how serious the problem is. Most hospitals now have whistle-blowing policies and Freedom to Speak Up Guardians, however there remains a valid concern that by reporting issues you will be seen as a trouble maker and unfortunately this may sometimes be true.

However unpleasant, it is essential that doctors stand strong if patient safety is at risk. It may seem like taking the moral high ground, but if we don’t alert management to patient safety issues, who else will take this responsibility?

At the Leicester Royal infirmary it is said other doctors knew there were problems with staffing and computer system failures but was this escalated within the Trust? Just verbally saying (complaining or grumbling) is not evidence; incident reports back up these statements?

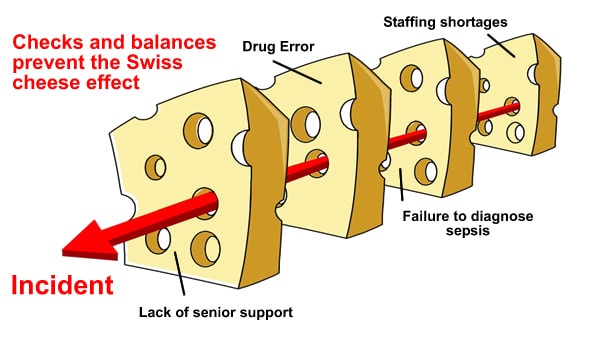

The Swiss cheese effect

Incidents and errors are often referred to as “Swiss cheese”. Swiss cheese has lots of holes in it but despite this if you look at a piece of Swiss cheese you cannot see through it; there is still some cheese in the way to stop you looking all the way through. This is the same as many near miss incidents. Something has gone wrong (a hole) but a check or balance has prevented the incident happening (a bit of cheese). Now imagine if all of the holes lined up and there were no checks or balances or bits of cheese to stop you looking all the way through; this is what happens in incidents. The whole system has failed. This is the thing about incidents; they are almost always due to system failures, not the fault of an individual.

I suspect we have all made mistakes and we have all been part of systemic failings in the NHS but the response to blame one individual means that rather than learning from mistakes and putting in place systems to prevent them from happening again, healthcare staff may try and hide mistakes and cover up incidents for fear of punishment. I’m sure, the public don’t have all the details and facts about the case of Dr Bawa-Garba but based on what is known, a terrible sequence of events occurred and a little boy died. If we want to stop this happening again we need to identify the failings and work to ensure they don’t happen again. My sympathies go out to both Jack Adcock’s family and to Dr Bawa-Garba; I actually think they have both been let down by the NHS.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed