The Oncology Registrar sat in the Multidisciplinary Team meeting looking thoroughly miserable. They looked like they hadn’t slept for ages, and whilst this can often be the case for junior doctors, the Microbiologist knew the registrar had only just returned from annual leave.

Whilst trying to pay attention to the patient discussions the Microbiologist watched as the poor Registrar kept scratching at his hands and arms.

As the meeting drew to a close, the Microbiologist wandered over…they can’t help but meddle!!!

“You look like your suffering” he said sympathetically, when in fact he was “itching” to make a shrewd diagnosis!!!

“Yeah. My hands and arms are really itchy, and it was worse in that room as it was so hot. I think I’m allergic to something”.

The Microbiologist wasn’t so sure.

“Show me your hands” he said.

The Registrar helpfully held out his hands which looked red and inflamed.

Looking closely whilst not touching (oooh, all those germs!!! He’d seen the Infection Control hand plates in the past!!!) the Microbiologist soon realised the likely cause of the problem.

“How did you know that?” asked the Registrar… and then the penny dropped.

“Oh no… it’s not scabies is it?!” he asked in a pitiful voice.

The Microbiologist just smiled…

What is scabies?

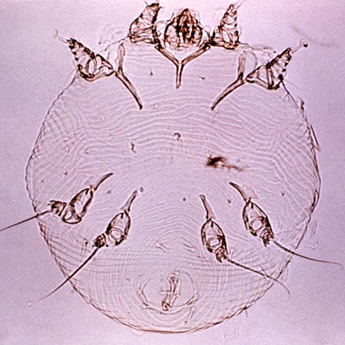

Scabies is the name used to describe an infestation with the Sarcoptes scabiei mite. Other Sarcoptes spp. can live on humans but as they cannot reproduce they soon die off.

Transmission of the mite occurs through either direct contact with infested skin (e.g. touching of hands or moving a patient etc.) or contact with skin scales containing the mite which have been shed into the environment (e.g. into bedding, clothes, towels, etc.).

How does scabies present?

Scabies usually presents with intense itching of the skin which is often worse at night. The patient frequently has small red papules or vesicles with associated linear red streaks (2-15mm long) which are the mites burrow. The itching is due to the delayed allergic inflammatory response triggered by the mite, eggs or mite faeces, and so symptoms usually don’t occur for 2-6 weeks after the first exposure but can be as little as 1 day if the patient has been previously sensitised.

The mite specifically likes softer skin so the most commonly affected sites are the finger webs, anterior surfaces of the wrist and elbow, the axilla and the belt line below the waist. Other sites that can be affected include the nipples, abdomen, lower buttocks and external genitalia in men. In children the head, neck, palms and soles can be affected.

Most patients with scabies have a total burden of 10-15 mites whereas patients with crusted scabies can have millions of mites!

How is scabies diagnosed?

Scabies is diagnosed by finding a mite in a papule. In my experience this requires some previous practice as the mites are small and can be difficult to find. It is best to choose a papule that has not been “attacked” by the patient’s scratching and then take a skin scraping for examination under a microscope in the microbiology laboratory. The laboratory will look for mites, eggs and even mite faeces (known as “scybala”…which looks like micro-mini deer poo… oversharing!?!).

How is scabies treated?

Scabies can be treated topically or orally.

Topical treatment is with Permethrin applied all over the body from neck to toes and under the nails. Permethrin should be left for 8-14 hours before being washed off. A further application is usual after 1-2 weeks to deal with any remaining mites and eggs. Permethrin is the first line treatment for children and pregnant and lactating women.

Oral Ivermectin 200microg/kg in two doses 1-2 weeks apart can also be used to treat scabies. It is considerably easier to use than Permethrin but it shouldn’t normally be used in children or in pregnancy or lactating women.

Crusted scabies is treated with a combination of both topical Permethrin PLUS oral Ivermectin. Permethrin is applied daily for 7 days THEN twice a week until the infestation is cured. The oral Ivermectin is given on days 1, 2, 8, 9 and 15 with further doses given on days 22 and 29, if infestation persists.

Itching may continue for 1-2 weeks after treatment as until all of the dead mites and eggs have been broken down and gone they will continue to stimulate the allergic inflammatory response. (Editor Chief in Charge is scratching now too!!)

How can outbreaks of scabies be prevented?

The best way to prevent outbreaks of scabies is to spot infested people early and treat them. In hospitals and other healthcare settings, close attention to hand-hygiene can also reduce the risks.

Patients with suspected scabies should be isolated in a side-room with their own toilet facilities until 24 hours has passed since starting treatment. For crusted scabies, as several treatments may be necessary to clear the infestation, isolation of the patient should be extended to at least 10 days after starting treatment. It is also good practice for staff to wear gloves and plastic aprons when caring for these patients.

It is important to clean all bedding and clothing of patients with scabies in a hot wash cycle of a washing machine and dryer, this is especially the case with crusted scabies, as the high heat is needed to kill both the mite and the eggs. At room temperature mites can survive off a host for 24 to 36 hours so unless transferred to a new host they will eventually die off in the environment. Therefore room cleaning is an important aspect of infection control in healthcare settings.

So the distraught Registrar was taken off to see a Dermatologist and get some treatment for their itchy mites. Rumour soon spread and after a while the phone rang and it was the Oncology Consultant…

“We have quite a few members of staff itching… do you think we have a problem?”

Sighing, the Microbiologist started scratching his chin thinking of how he was going to tackle this particular outbreak... and then he realised he was scratching his chin…! Thinking quickly, had he actually touched the hands of the Registrar?!? Are you itching yet…?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed