The microbiology laboratory I work in is one of the biggest in the country and it processes about 1.5 million samples per year. That’s 1.5 million results. Do I think we get every one of those results correct… no. That would be unrealistic and I’m not that gullible (or fabulous!). Even if we were only wrong once in every 10,000 samples (0.01%) that would still be 150 errors a year. Which seems a high number, I think you’d agree? I suspect mistakes occur daily in the NHS.

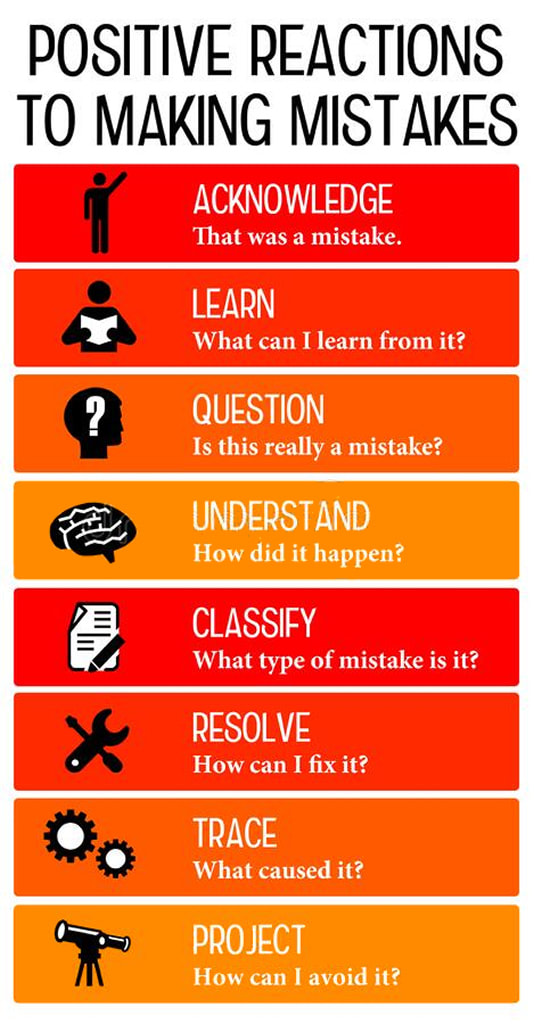

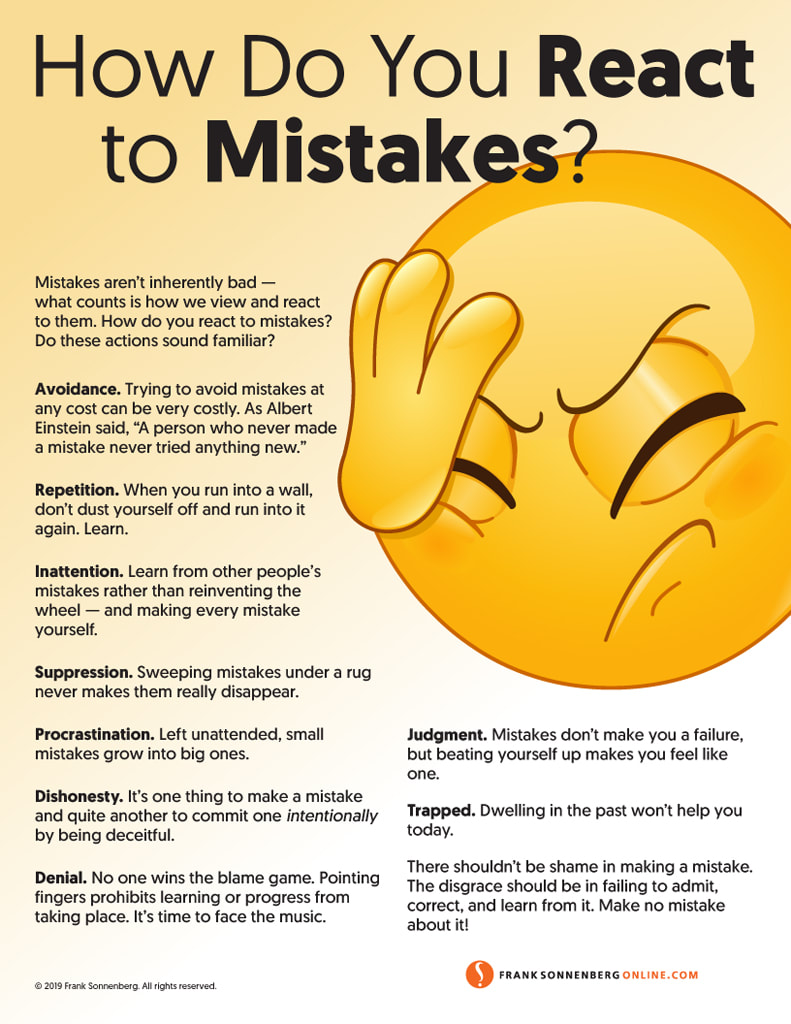

The key to errors in medicine is to reduce them to as low as possible by recognising that they occur and learning from them when they do.

In order to do this, we use tools like incident reporting, root cause analysis (RCA) and serious incident investigations. The aim is to make sure the same mistakes don’t keep happening.

In 2013, the Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry was published; this is often known as the Francis Report after the chairman of the inquiry, Robert Francis QC. The inquiry looked at the horrendous care of patients at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust and amongst it’s conclusions a number of key issues were noted.

The Trust put national targets, financial balance and its Foundation Trust application above patient care. They ignored concerns about patient care, failed to learn from errors and failed to tackle problems raised by staff. It is a damning report!

As part of the recommendations from the Inquiry a key point is that healthcare organisations should have an openness, transparency and candour where patient safety concerns are raised.

The basic upshot of this is that organisations now have a legal responsibility to admit when things go wrong, without necessarily admitting some form of guilt, and then investigate and learn from what happened.

The Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust midwifery has been through a similar independent review (2020 & 2022) and showed lessons were not learnt, the final report is now published and it found that the Trust “failed to investigate, failed to learn and failed to improve and therefore often failed to safeguard mothers and their babies”. The review commenced with 23 families’ cases, but it grew to include reviews of nearly 1,500 families! Added to this, there are a lot of smaller incidents also occurring in the NHS (I’d suggest daily) and these don’t make the headlines or get independent reports. We need to acknowledge mistakes and be open and transparent in our investigations and learning.

The patient

A patient is seen in a hectic Emergency Department with cough and shortness of breath on lying down and waking in the night short of breath. They have a chest X ray which is interpreted as showing bilateral pneumonia. They are given a course of Amoxicillin and sent home and told that they are going to feel unwell for quite a few weeks and not to be too concerned about this.

After a brief period of feeling a bit better the patient starts to feel worse again. They go to their family doctor who looks at the hospital summary and thinks that maybe they didn’t have a long enough course of the antibiotics and so prescribes a further week of Amoxicillin.

Again, the patient feels a bit better for a while, and then one morning they feel awful. Their partner notices that they are having trouble getting out of bed. They are slurring their speech and part of the face is drooping. The partner immediately realises that the patient is having a stroke and calls an ambulance.

In the hospital the patient is diagnosed with an embolic stroke and has a scan of their heart that shows a large clot on their aortic valve which has a big hole in it allowing blood to flow backwards into their lungs. As the patient has a low-grade fever a blood culture was done, and it grows an Enterococcus faecalis.

Now, you may look at this story and see an unfortunate series of infections in the patient, but I don’t, but then I’m suspicious like this. I see a number of missed opportunities to make an early diagnosis of infective endocarditis and prevent the stroke!

The story

The key to almost any diagnosis is the story. In this patient’s case there are alarm bells that there was more to his story than just pneumonia. If I was to be involved in an investigation into his care these are the basic points I would pick out to explore further:

- Shortness of breath on lying down or waking short of breath – these are called orthopnoea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea respectively. Basically, they tell you that when you take away orthostatic pressure from gravity keeping the lungs empty of oedema, they fill up with fluid and the patient can’t breathe. Yikes…They are a sign of severe heart failure not pneumonia!

- Bilateral consolidation – bilateral pneumonia is uncommon, and having chest x-ray changes in both lungs is more in keeping with heart failure than pneumonia

- Clinical signs suggesting heart failure responding to antibiotics – if the patients’ symptoms were only due to heart failure the antibiotics shouldn’t make a difference. The fact that they do means an infection is making the heart failure worse… the question then would be, what or where is the infection?

- Why are two courses of antibiotics not enough to cure the patient – most cases of pneumonia will respond to a week of antibiotics (Amoxicillin), and yet this patient relapsed twice. This should raise an eyebrow or trigger inquisitiveness, if not an alarm “we’ve got something wrong here!” It implies it is not pneumonia but a much deeper source of infection.

When you combine the severe heart failure, bilateral chest X-ray changes, temporary response to Amoxicillin and the bacteria that would respond to this antibiotic it becomes likely that the patient actually has infective endocarditis causing heart valve destruction and pushing them into heart failure. The 3 most common bacterial causes of infective endocarditis are Viridans streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis. Of these the Viridans streptococci and E. faecalis are sensitive to Amoxicillin.

So, even without the patient having a stroke and then positive blood cultures and a scan that shows a vegetation we can tell from the story what is going on, and even have a pretty good idea what the causative bacteria might be.

However, because we have failed to interpret the signs correctly the patient has gone on to have a stroke; a serious and life changing complication of the infection. And so, the question is “if we had intervened earlier and treated properly could we have prevented the stroke from happening?”

The investigation

Trust’s have something called incident reporting, where anyone within the organisation can report a situation where they believe something has gone wrong and that either it has “nearly” caused harm (known as a near miss) or has “actually” caused harm. It is imperative that everyone feels safe when incident reporting and that raising concerns will not result in the Trust taking any action against them. (This was also something that came out of the Francis Report where staff were targeted for reporting concerns).

If we were to do a Root Cause Analysis (RCA) on this incident and look to where things went wrong, we would identify a number of failure points:

- Incorrect interpretation of the symptoms

- Incorrect interpretation of the chest X-ray

- Wrong diagnosis

- Failure to recognise why the patient relapsed after initially responding to the antibiotics

There might be others. Did anyone examine the patient for signs of endocarditis like splinter haemorrhages or a heart murmur, was the patient febrile when they were seen in the Emergency Department and should they therefore have had blood cultures taken earlier which would have identified the bacterium prompting earlier scans, did the patient have other signs suggesting a more chronic infection such as weight loss or night sweats? The list could be long, and each is a potential missed opportunity to make the correct diagnosis.

The outcome

So, what would be the outcome of this investigation?

Firstly, there is a legal Duty of Candour on the Trust to explain what has happened to the patient and apologise. This isn’t an admission of any wrongdoing at this stage as the investigation may not be complete. It is a recognition that something bad has happened to the patient and that the Trust is going to investigate to see whether this could have been prevented.

After the investigation the patient should be told of the findings and what the outcome is going to be. They should also be given information for how they might proceed to a complaint if they want to do so. They should also be told what the Trust will do to try and prevent this from happening again; this might be in the form of further training for those involved.

At the end of the process a report should be written, and the Trust should demonstrate how it has learnt from the process.

So, at the end of the process the Trust must learn and make changes. If it doesn’t and the same thing keeps happening then the Trust will be held responsible for the harm it is allowing to happen. Incident reporting and investigating incidents is the process by which the healthcare service should learn and make changes to protect patient safety. It is not comfortable, it can be difficult and unpleasant to do, but it is very important, and a key part of healthcare.

The key question for us as healthcare professionals is how do you “see” incident reporting, how do you “feel” about investigating incidents and how can we all “foster” more openness, transparency and candour when patient safety concerns are raised. Are we all doing enough to create that “inquisitive atmosphere” so often needed to stop an incident occurring?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed