The patient had not been able to get an immediate appointment with their GP and so had come to A&E a couple of days ago, despite their problem not really being an Accident or an Emergency. Stool samples had been sent to the lab on the first visit and the A&E doctor was following up the results as the patient had returned to the department with ongoing symptoms. The A&E doctor was calling the Microbiologist because no cause of the diarrhoea had been identified on the lab report.

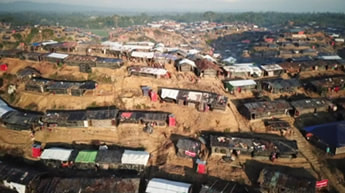

Violence erupted in Rakhine in late August when Rohingya militants attacked security posts, triggering a military response. More than half a million Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh to escape the campaign of killings and village burnings, refugees in Cox’s Bazar number close to 700,000 people, making this the world’s largest refugee camp. Cholera disproportionally impacts communities already burdened by conflict, lack of infrastructure, poor health systems, and malnutrition.

Infection occurs as a result of the toxin produced by V. cholerae binding to the small bowel wall which in turn causes massive fluid and electrolyte transfer into the gastrointestinal lumen.

How does cholera present?

Cholera kills an estimated 95,000 people and affects a further 2.9 million more every year. Of these it is estimated that more than 50% of cholera is asymptomatic and many cases go unreported.

Cholera gastroenteritis presents with:

- Profuse watery, painless diarrhoea (known as rice water stool because it looks like water that has been used to cook rice)

- Nausea and vomiting

Severe infections cause:

- Dehydration

- Shock

- Hypoglycaemia

- Acidosis

- Renal failure

- Death

The incubation period is usually 2-3 days but can be as short as 12 hours and up to 5 days.

Most cases of cholera occur in the context of either extreme poverty with poor sanitation or humanitarian crises leading to large numbers of refugees living in poor sanitary conditions. Over two billion people worldwide still lack access to safe water and sanitation putting them potentially at risk of cholera.

Most Microbiologists are aware of the story of Dr Jon Snow, who in 1854 in Soho, London, traced the cause of a cholera outbreak to the Broad Street water pump and abolished the outbreak by removing the handle of the pump to stop people consuming contaminated water. This was a remarkable achievement as bacteria had not yet been shown to cause disease and so Dr Snow did not know the cause of cholera, he just worked out where it was coming from through careful questioning and observation (the key to good medicine really). It turns out that the well for the Broad Street pump had been dug within a few meters of an old cess pit and faeces from the cess pit had leaked into the well… the rest as they say is history.

During the 19th century cholera was the scourge of Asia with 6 pandemics spreading worldwide from the Bay of Bengal. In 1961 a 7th pandemic occurred with spread from Asia to Africa in 1971, and then to the Americas in 1991. This pandemic was caused by a new serogroup O1 strain called “El Tor”. Since then there has been emergence of another serogroup in Asia called O139, it has never been identified outside Asia. From 2001 to 2009 more than 90% of cholera (and almost all of the cholera related deaths) actually occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa.

In recent history there are two notable outbreaks. The first following the earthquake in 2010 in Haiti, which left a large proportion of the population homeless and living in poor sanitary conditions. Within 2 years there were over 600,000 cases and 7,500 deaths, in a population of just over 10 million. In 2012 half of the cholera in the world occurred on this small Caribbean island.

More recently an outbreak of cholera has occurred in Yemen with over 800,000 cases reported and more than 2000 deaths since April 2017. Suspected cases continue affecting an estimated 5000 people per day as millions of people are cut off from clean water, and waste collection has ceased in major cities.

Currently the WHO is implementing a mass vaccination program in Bangladesh in order to control another mass cholera outbreak in the Rohingya refugee camps. The WHO acknowledges that in both these outbreaks the answer is not only improved basic sanitation infrastructure and healthcare support but to find a political solution to conflict.

In early October a Global Task Force of over 50 United Nations and international agencies, academic institutions, and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) launched a new joint strategy to combat cholera, aiming to reduce deaths by 90 per cent by 2030. The WHO say “every death from cholera is preventable with the tools available today, including use of the oral cholera vaccine and improved access to basic safe water, sanitation and hygiene”.

How is cholera diagnosed?

In the developed world cholera is diagnosed by culturing V. cholerae from a stool sample. Specific culture media is required, called Thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose agar (TCBS for short), and because cholera is rare in these developed countries it is not routinely tested for. It is imperative that good clinical information is provided with the request for stool culture, especially a travel history as well as duration of symptoms, contact with others who have similar symptoms and any risky pastimes e.g. water sports.

If the patient might have typhoid or paratyphoid the sample should be labelled HIGH RISK to help protect the laboratory staff from acquiring infection from the sample or culture. Once a V. cholerae has been cultured it should then be tested for O1 and O139 antigens and sent to the reference laboratory to look for the production of toxin.

In the context of a cholera outbreak only representative stool samples need to be tested to make sure the cause of diarrhoea hasn’t changed and antimicrobial sensitivity can be done. During an outbreak a simple case definition (see previous blog on Norovirus at the World Athletics Championships – what is an outbreak) that includes symptoms of cholera plus potential exposure to contaminated water would be enough to make the diagnosis.

How is cholera treated?

The treatment of cholera is relatively straight forward in principal but in practice it is not so easy. Almost all cholera deaths could be prevented with adequate rehydration of the patient and more than 80% can be treated with oral rehydration solutions (ORS) – you know them, the slightly salty lemon or blackcurrant powders travellers are told to take if they get diarrhoea. The problem is that the clean water needed to make up the ORS may not be available (it’s ironic that the treatment requires clean water as if they had that the person probably wouldn’t have acquired cholera in the first place!). Severe infection requires IV fluids but these are expensive and require expertise to be given safely, and all of this usually occurs in resource poor countries or areas of humanitarian crisis where getting even basic supplies can be almost impossible.

Mild infections: treat with ORS to replace estimated fluid loss (rate of loss x 1.5 per day). Zinc supplements reduce severity and duration of illness in children less than 14 years of age.

Severe infections: require initial rapid IV rehydration followed by ORS replacement. Antibiotics are also given to reduce the duration of illness and reduce the amount of rehydration required. Commonly used antibiotics include Doxycycline, Ciprofloxacin, Erythromycin or Azithromycin, but antibiotic resistance is an increasing problem and therefore antimicrobial sensitivity testing should be undertaken on representative outbreak strains to guide treatment.

How can cholera be prevented?

The most important way to prevent cholera is to provide safe drinking water and sanitary disposal of human waste. However, this is not easily done in the situations where cholera occurs; poverty and humanitarian crises.

Another way to prevent cholera would be through mass vaccination in at risk groups. There are now 3 cholera vaccines which cost just US$6 per person, Dukoral®, Shanchol™, and Euvichol® available through the WHO. “The introduction of the oral cholera vaccine has been a game-changer in the battle to control cholera – bridging the gap between emergency response and longer-term control…with oral cholera vaccines now available, individuals can be fully vaccinated for up to three years of protection,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization.

However two doses of vaccine are required to prevent about 65% of cases of cholera, so although a breakthrough in outbreak management, they are not a replacement for safe drinking water.

Rapid treatment of cases and protective vaccination will help limit the spread of infection. Alongside this, infection control precautions using gloves and aprons for contact with infected body fluids, hand hygiene and safe disposal of faeces, are required to prevent ongoing transmission. Once an outbreak has occurred it is essential that clean water and sanitation are provided as quickly as possible.

So the patient’s stool sample was cultured on TCBS and the next day V. cholerae was grown. This was subsequently shown to be an O1 El Tor strain with cholera toxin. Because the patient just had mild diarrhoea he was advised to continue to drink ORS until his symptoms resolved. He was advised that he would be infectious for up to 5 days after his symptoms resolved so to continue to implement basic hand hygiene and infection control measures. He did not need antibiotics.

And the A&E doctor never left the clinical details box on the laboratory request form blank again…

RSS Feed

RSS Feed