You have to admit, it’s not great PR to be associated with the scariest viruses known to cause deadly human infections. But is this fair? Are bats really MORE likely to be the source of infections in humans? Do bats harbour more nasty viruses than other animals? Or are they just getting a bad press and we should cut them some slack?

And yet there appear to be a lot of bat viruses that cause disease in humans…

Why are there a lot of bat viruses affecting humans?

The reason that there appear to be a lot of bat viruses affecting humans is that there are a lot of different bat species; lots of different types of bats means lots of different viruses.

Research has shown that when you look at the extent of variation within bird and mammal species there is no single species that is more likely to cause zoonoses than any other. In fact the relationship is linear as shown in the graph below (Mollentzea and Streickera); the more subspecies there are within an animal group the more viral zoonoses there are. Bats cause a lot of zoonoses because there are lots of different subspecies of bats and therefore there are lots of different bat viruses.

So it isn’t the species itself that’s the risk factor for zoonotic infection but rather the biodiversity within a habitat; more animals = more microorganisms = more zoonoses.

But it can’t just be about the number of species can it?

Okay, so there might be other factors at play as to why bats get such a bad press.

One reason is that these “bat viruses” are particularly nasty. Let’s consider the mortality from the best known:

- Rabies 100%

- Marburg 90%

- Ebola 70%

- Nipah 70%

- Hendra 50%

- Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) 35%

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) 10%

The mortality from these diseases is very high, “Killer Disease” headlines, and that doesn’t even take into account the widespread chaos that can result; just look at the global reaction to recent Ebola outbreaks or the financial crisis of Covid-19. But this isn’t a “feature” of the bats but rather the “viruses” themselves. They are just bad viruses for humans, which are just some of the bats’ “normal flora”. These “viruses” are highly virulent and transmissible but that’s not the bats fault!

There are plenty of other bad zoonoses which have close to 100% mortality if untreated including African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), visceral leishmanisis and pulmonary anthrax (which can all be transmitted either via tsetse fly, sand fly or directly from infected domestic and wild animals) and yet these “Killer Diseases” don’t have the same bad reputation of the bat zoonoses (oh! was it cos you hadn’t heard of these ones?!! ARGH, panic!!)

Are we prejudiced?

I think part of the reason that societies centre the blame on bats is due to the fact that lots of people find bats creepy and unpleasant. Historically they have been the “bad guys” in popular culture e.g. often seen as a ghost, shadow of darkness or a separate soul, vampire bats were used in folklore to discourage people staying out late, seeing one meant death or destruction was sure to happen in their near future, and then there’s the blood drinking villain in Dracula who was able to turn into a bat to evade capture. The Chinese on the other hand believe bats are associated with happiness and longevity. Then there’s Count Duckula…who didn’t love him?! And Batman’s a superhero…

Human nature appears to apportion blame where we can and bats make an easy target. Generally they aren’t a cuddly cute looking animal either, they only come out at night and they live in caves and other dark places… OK I get the concerns.

Should we be batty about bats?

There are some of us who actually think they do possess some cuteness, are thrilled to see them take flight in mass at dusk, are amazed that they can hunt in the dark using echolocation and are excited to see them when exploring the places where they live. Personally I think they’re amazing and think we should care for them more! They are a protected species here in the United Kingdom.

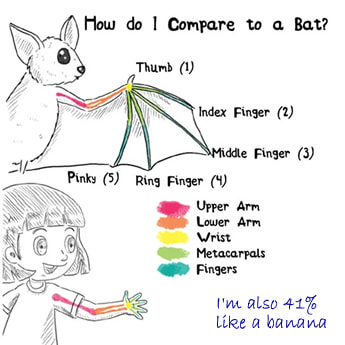

Did you know there are over 1,400 different species of bats worldwide; making up about 20% of all mammal species? And within the bat species there is a huge amount of diversity and they are the only mammal which can fly. At one end of the scale we have flying foxes with a wingspan of up to 2m weighing 1.5kg, and at the other end there are bumblebee bats the size of bees weighing just 2g! Bats have different dining habits too, from blood to insects, to fruit and pollen. They are truly an amazing group of mammals!

There is another school of thought as to why bat viruses transfer into humans and that is to do with the environment, or more specifically our constant destruction and invasion of the different habitats.

For a bat virus to cross into a human there usually has to be close proximity between bats and humans. This tends to happen when humans push into the bats habitat, trade in wildlife, cut down the forests and destroy bat roosting places. This forces the bats to use human dwellings as roosts, and forces bats to use farms and plantations as food sources, which all bring bats into closer contact with humans.

This doesn’t just apply to bats. If we push into new habitats we will eventually become exposed to new microorganisms that we, as a species, haven’t been exposed to before. This is exactly what has happened with the coronaviruses SARS Virus, MERS Virus and SARS Cov2. These viruses were probably not “new” but we humans hadn’t come into contact with them before; when we did we had no immunity to them and we became sick.

Again this isn’t the fault of the rodents, pigs, birds or bats; if anyone is to blame it’s us, humans. Our increasing population, our need for more agricultural land to feed this growing “meat-eating” population and the demand for products (soy, beef, palm oil), that come from this land means we are “evicting” more and more animals. We are forcing the animal contact and increasing the likelihood of zoonotic exposure to new microorganisms.

What does this all mean?

Current policy with regards to pandemic awareness and tracking of potential zoonotic agents is currently targeted at high risk animals or “special reservoirs” such as bats, birds, pigs and rodents but this probably isn’t really the right approach? The “special reservoir hypothesis” is that physiological or ecological traits of these animals make them more likely to maintain zoonotic viruses or transmit them to humans. Whereas the “reservoir richness hypothesis” believes host species maintain a similar number of viruses with a similar per-virus risk of zoonotic transmission. Variation in the number of zoonoses among animal groups e.g. rodents and bats arises as a consequence of their species richness, rather than the species alone.

It would be wrong to ignore animals we know carry zoonotic diseases but what some scientists are proposing is that we should be looking at highly biodiverse places where there is close contact between humans and nature. On these margins where humans and lots of animals meet, like jungles and forests, we need to invest in research and make sure we look at the human pathogenic potential of the microorganisms we find. Globally we should see the investment as an insurance policy; if we invest the millions now we won’t have to pay the trillions later… if nothing else Covid-19 should have taught us this lesson.

DO NOT HANDLE BATS… it’s not good for you but more importantly it is not good for the bat! It also illegal to do so without a license in the UK.

- Bat Conservation Trust https://www.bats.org.uk/

- Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Nardus Mollentzea and Daniel G. Streickera Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) 2020; 117 (17): 9423-9430

RSS Feed

RSS Feed