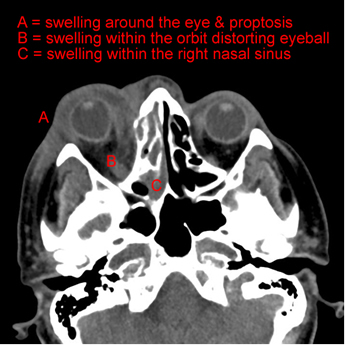

The Microbiologist noted that she was iron overloaded as a result of her frequent blood transfusions and given her clinical presentation of cellulitis unresponsive to antibacterials, proptosis and black palate made a provisional diagnosis of mucormycosis. An urgent MRI showed oedema of the orbital tissues and nasal sinus involvement. Posaconazole was added to her treatment and it was strongly advised that she have surgical decompression and resection of the infected material in her orbit.

Mucormycosis is the name given to the infections caused by the group of fungi called the zygomycetes (or sometimes the mucorales). These filamentous moulds cause opportunistic infections, exploiting particular situations in order to colonise patients and then invade to cause infections. The zygomycetes are environmental microorganisms found throughout the world.

When should you think about mucormycosis?

Mucormycosis is rare! When it does occur it tends to affect patients in four specific groups:

- Immunosuppressed, e.g. prolonged neutropaenia for weeks or months

- Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus

- Iron overload e.g. frequent blood transfusions for chronic anaemia

- Prolonged corticosteroid administration for weeks or months

If any patient in the above groups presents with an illness consistent with mucormycosis (see below) or has ongoing pyrexia despite adequate antibacterial cover then invasive fungal infections including mucormycosis should be considered even though it is rare.

How do patients with mucormycosis present?

Typical clinical presentations are related to the mode of acquisition (airborne or ingested) and localised spread into the blood vessels and soft tissue. There are four main presentations:

- Rhinocerebral, infection begins after spores germinate after settling in the nasal passages and extends up into the head and down into the palate, causing destruction of the bones of the sinuses and skull, space occupying lesions, brain haemorrhages, strokes and blackening of the palate. Occasionally these lesions extend in to the orbit causing damage to the eye and its surrounding soft tissues leading to proptosis (protruding eye ball)

- Pulmonary, infection occurs when spores germinate after settling in the lungs causing tissue damage and pulmonary infarction

- Gastrointestinal, infection occurs after ingested spores geminate in the bowel and then erode through the gut wall and its associated blood vessels leading to bowel ischaemia and peritonitis

- Cutaneous, infection occurs when spores settle and germinate in wounds or other breaks in the skin then extend further into the skin and muscle, extending along the fascial planes as well as invading local blood vessels causing infarction of soft tissue

How do you diagnose mucormycosis?

Having blogged about the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections last week anyone who has managed to get hold of the British Society for Medical Mycology guidelines will realise that where mucormycosis is concerned we have very little to offer. At present if mucormycosis is suspected then the best ways of proving the diagnosis are by either growing the fungus or seeing it in histopathological specimens. In my experience they can be difficult to grow in the laboratory and therefore histopathology is the best bet. If you can get them growing in the laboratory they are pretty dramatic, spreading a centimetre a day and easily filling up a petri dish within 48 hours (if you don’t want those spores spreading to other samples nearby then its best to put sticky tape around the seal between the bottom and top of the petri dish otherwise they will start to push the lid off!!).

How should mucormycosis be treated?

Even as little as 10 years ago a diagnosis of mucormycosis was pretty much a death sentence. Treatment with surgical resection and high doses of liposomal Amphotericin B preparations only managed to save about 10% of the patients infected, and I suspect those that did recover actually got better because they had a reversible underlying reason for why they were at risk e.g. they were on long-term corticosteroids and these drugs could be stopped.

This dire situation changed with the introduction of the azole antifungal Posaconazole. In the clinical trials Posaconazole was used as rescue therapy for patients who were failing “conventional” therapy with surgery and Amphotericin B and would have died without another treatment. Of these patients 70% got better with Posaconazole; finally Microbiologists had something to offer patients with mucormycosis! There were some added bonuses to this new treatment: Posaconazole is oral whereas Amphotericin B is intravenous and Posaconazole isn’t nephrotoxic whereas Amphotericin B is.

From my own experience I have now managed five patients who had confirmed mucormycosis (3 rhinocerebral, 2 pulmonary...but I do like looking for rare diagnoses!) with Posaconazole and all five have survived. It may not sound like much but for such a rare condition this is quite a few and I’m convinced that Posaconazole is the right treatment.

Outbreaks of mucormycosis

Investigators of outbreaks are becoming more aware of the potential for the environment to be sources of infection especially with unusual organisms. Environments which have had a period of humidity and warmth followed by drying out allow fungi to germinate facilitating spore formation and airborne spread. I like to think I helped start a bit of a trend in this respect by successfully investigating and stopping an outbreak of mucormycosis in a paediatric oncology unit related to water damage to a linen cupboard on the ward (Microbiologists hide in all sorts of places, especially warm ones!) Maybe I’ll blog about that in the future...the outbreak not the places Microbiologists hide!?!

Back to the lady with the orbital cellulitis; she required surgery to resect the infected material. The laboratory managed to grow a zygomycete and this was also seen on histological examination. The patient was started promptly on Posaconazole and her fever settled and the cellulitis improved but unfortunately, due to the angioinvasive nature of the mould, clotting of the blood vessels supplying the eye lead to infarction of the eye itself. The patient had to undergo an enucleation (removal of the eyeball and associated structures). Bitter sweet but without Posaconazole I fear it could have been a far worst outcome. After 6 weeks the MRI showed the infection had cleared and the Posaconazole was stopped. However, given her ongoing risk of infection due to iron overload she was started on iron chelating therapy to try and prevent future occurrences.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed