What is Naegleria fowleri?

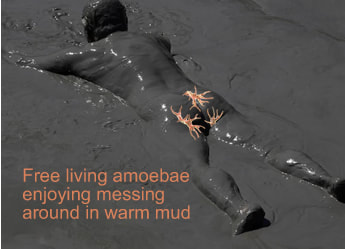

Naegleria fowleri is a free-living amoeba found in freshwater and soil throughout the World, preferring temperatures between 30-45 oC. It does not survive in seawater. The most common risk factor for acquiring N. fowleri is contact with water through sports such as swimming, water skiing and diving as well as messing around in mud or bathing in contaminated hot springs (it is “free-living” after all!). So this explains my curiosity as to how this patient had acquired their infection as it should be very difficult to “get exposed” to N. fowleri during a lockdown, because there wouldn’t be any water sports or other exposures going on at this time!

Apparently another, less common, way to acquire N. fowleri is by using contaminated tap water for sinus irrigation… if for some reason tap water is going to be used for irrigating you sinuses it should be boiled for at least a minute and allowed to cool to kill off any microorganisms before-hand. As someone who hates getting water up my nose even in the shower I find just writing this is making my eyes water!!! [...but the bit about a brain penetrating amoeba doesn’t?? ECIC]

There is a concern that with global warming the number of N. fowleri infections will increase because water temperatures will increase and this amoeba especially likes warmer water!

How does infection with N. fowleri present?

Infection with N. fowleri results in a condition called primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). Patients experience a severe headache, neck stiffness, fever, photophobia (pain on exposure to light), vomiting, seizures, altered consciousness and often also suffer olfactory hallucinations (they “smell” and “taste” things that aren’t actually there! …weird hey!).

The disease progresses rapidly, on average up to 5 days, with increasing intra-cranial pressure leading to herniation of the base of the brain through the base of the skull (known as coning) which is fatal. The mortality from PAM is 99%, which is really bad, especially as the incubation period is only about 5 days, and your physician probably won’t have heard of it or thought of it as a diagnosis until it’s too late.

BUT, before you all start panicking and thinking here’s the next “global outbreak” let me reassure you; PAM is extremely rare! There have only been an estimated 300 cases since it was first described in Australia back in 1965. However exposure to the amoebae in some areas of the World such as Southern USA is very common; with evidence of exposure demonstrated by the presence of antibodies. No one knows why some people get a horrendous infection and yet most just have asymptomatic exposure. But this rarity is another reason for the case catching my eye.

How is PAM diagnosed?

The crude answer to this is “with great difficulty”. PAM is hard to diagnose given its rarity… it usually wouldn’t be thought about until it is too late to do anything about it. In fact most cases of PAM are diagnosed post-mortem!

In order to diagnose PAM you have to think about it. So what would make me think about PAM? Some clues would include:

- History of exposure to water in the week leading up to the onset of meningoencephalitis, especially if that water was likely to be warm e.g. returning traveller… not bath tub users!

- CSF – high neutrophil count, very low glucose, high protein, very high CSF pressure, yellow/white or grey or haemorrhagic appearance

- Negative bacterial culture and negative bacterial and viral PCR on CSF

- No-response to antibacterial and antiviral drugs targeting the common causes of meningoencephalitis e.g. Ceftriaxone PLUS Amoxicillin PLUS Aciclovir

Confirming the diagnosis requires identifying the amoeba in CSF. Traditionally this has been by seeing trophozoites of N. fowleri in a wet preparation of fresh CSF that has been centrifuged to concentrate the CSF; they look a bit like white blood cells so it takes an experienced eye to recognise them. An alternative to this microscopy is PCR on the CSF for N. fowleri; although this is not widely available and in the UK would be done by the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, London.

However, it would probably take at least 2-3 days at best to get all of the above results back and to judge that the patient wasn’t responding to treatment and so the diagnosis is still very likely to be made too late.

So this got me thinking to why else would I as a Microbiologist notice a case of this rare infection? I think the main reason it caught my eye is that it is one of these conditions that Microbiologists “know about” because they know if they don’t think about it as a possibility in a patient then no one will… not to mention it’s one of those “clever diagnoses” competitive Doctors like to make! [You mean they are Micro-Nerds!? ECIC]

How is PAM treated?

Given the rarity of the diagnosis and the fact that most cases aren’t diagnosed until too late there is no single recommended antimicrobial regimen for PAM. Treatment is based on observations and experience from treating other amoebic infections such as acanthamoebiasis and the choices of agents are a bit counter intuitive.

One such regimen includes:

- Liposomal Amphotericin B (an antifungal)

- Fluconazole (another antifungal)

- Miltefosine (an anti-parasitic used to treat Leishmania)

- Azithromycin (a macrolide antibacterial)

- Steroids (to damp down the inflammation and swelling in the brain)

Weirdly there is only one anti-parasitic agent. Treatment is often continued for about 4 weeks, but this is not evidence based, as in reality only 11 survivors have been described in the medical literature and all had different treatments! There is no news yet as to the outcome for the latest patient from Florida but it’s a grim diagnosis.

Infection Control

There are no specific infection control procedures for N. fowleri as it cannot be passed from person-to-person; although there are concerns for the possibility of transmission if organs are transplanted from a person who dies from this infection e.g. patients who have died from what was thought to be bacterial meningitis when in fact the infection was actually N. fowleri.

So in Florida there has apparently been advice from the local Department of Health to:

- Avoid water-related activities in bodies of warm freshwater, hot springs, and thermally-polluted water such as water around power plants.

- Avoid water-related activities in warm freshwater during periods of high water temperature and low water levels.

- Hold the nose shut or use nose clips when taking part in water-related activities in bodies of warm freshwater such as lakes, rivers, or hot springs.

- Avoid digging in or stirring up the sediment while taking part in water-related activities in shallow, warm freshwater areas.

This is all nice advice but how practical is it considering they cannot get people to obey their Covid-19 lockdown rules… over 10,000 Covid-19 cases in one day, that’s a lot of Covid-19 and not a lot of social distancing!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed