The most important part of the assessment of fever in a returned traveller is the history. The essential components of the history are:

• Where have they been, for how long, and was it rural or

urban?

• Have they had any contact with animals and insects?

• Have they been exposed to anyone else ill and how long ago was it?

• How long have they been unwell and when did it start?

• Have they received immunisations including both the primary childhood course and travel related?

• Did they take malaria prophylaxis? What and for how long?

These questions indicate what infectious organisms the patient might have been exposed to, what might be included in a differential diagnosis and therefore what specific investigations and specimens are required.

Firstly, where have they been? What on earth could they have picked up?!

Whilst it is intellectually stimulating, and not to mention good for the ego, to make a clever diagnosis of a weird tropical infection, most patients who present with a fever having been abroad actually have something much more mundane. The most common diagnoses in these patients are actually the same kinds of infections they would have acquired had they never left home (e.g. pneumonia, urinary tract infection and cellulitis). The patient’s travel history is often unrelated to their illness.

As a matter of routine, all returned travellers who present to

hospital with a fever should have the following investigations IN ADDITION to any disease specific investigations based upon travel destination.

• Full blood count

• Urea & electrolytes

• Liver function tests

• Blood cultures

• Midstream urine

• Chest X-ray

And finally, don’t forget to treat for life-threatening

infections first!

It is important to remember to treat empirically for any

potentially life-threatening infections whilst waiting for “tropical” investigation results. For example, it would be wrong not to treat a septic patient with broad spectrum antimicrobials whilst waiting for malaria, dengue and enteric fever investigations.

BUT don’t ignore the travel history either! A patient with meningitis who has been to a malaria endemic area should be treated for both normal bacterial meningitis and cerebral malaria.

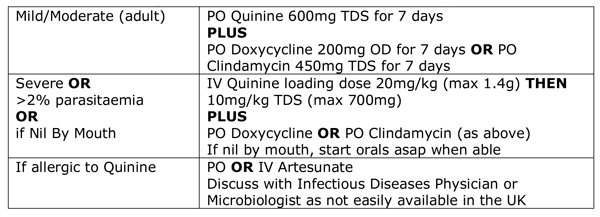

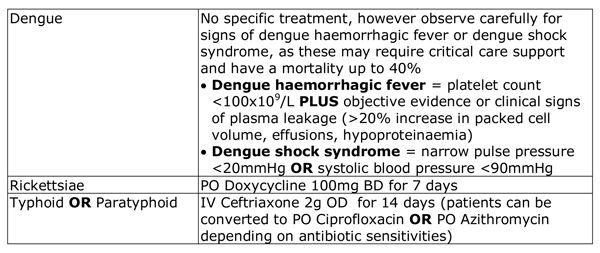

The treatments for the most common tropical infections in adults are shown below: for children seek advice from an Infectious Diseases Physician or Microbiologist.

Treatment for falciparum malaria OR unknown

malaria species

Discuss with an Infectious Diseases Physician or Microbiologist.

diagnose. However, diagnosing them is often unnecessarily complicated, investigations are haphazard and differential diagnosis lists are often incomplete or even random!

Remember these 4 key points and you’ll find diagnosing, investigating and treating tropical infections far simpler and much more satisfying.

- Take a detailed travel history to identify what they might have acquired

- Send the correct specimens for the potential diagnoses

- Remember “common things are common” don’t forget UK acquired infections

- Don’t forget to treat life-threatening infections whilst waiting for “tropical” investigation results

Download a handy postcard of the infections related to travel destinations and their investigations and keep it in your book "Microbiology Nuts & Bolts"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed