This is no coincidence; the common bacterial causes of meningitis include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae all of which colonise the URT and if the upper respiratory tract becomes inflamed, these bacteria can invade more readily. The most common reasons for inflammation in the upper respiratory tract... you’ve guest it, are viral infections. So as your cases of virus induced illnesses goes up don’t forget to put a reminder in your diary for potential meningitis in 2 weeks time! So let’s discuss how to diagnose meningitis, and in particular how to interpret cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) results.

Some of these are generic to most infections, e.g. fever, but others are specifically related to inflammation of the meninges, the fibrous tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

Clinical features associated with inflammation of the meninges include:

• Fever

• Headache

• Photophobia (intolerance of light due to increased headache and eye pain)

• Neck stiffness

• Pain on extension of the leg (Kernig’s sign)

• Decreased conscious level

• Confusion

• Seizures (30% of patients)

• Focal neurological signs

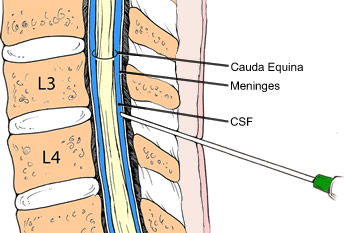

If the clinical features suggest a possible diagnosis of meningitis then the most important investigation is a lumbar puncture (LP) in order to acquire a CSF sample. The CSF lays inside and next to the meninges and so any inflammation or infection of the meninges will result in abnormal CSF.

3+1+1 = A correctly taken CSF sample:

A correctly taken CSF sample consists of 5 tubes:

• 3x CSF in sterile universal containers (labelled 1,2,3)

• 1x CSF for glucose in a fluoride oxalate tube (grey vacutainer tube)

• 1x peripheral blood for glucose in a fluoride oxalate tube (grey vacutainer tube)

The universals should be numbered and taken in that order. Put 0.5-1ml of CSF in each universal and the same amount into one of the fluoride oxalate tubes. Next, and very importantly, do not forget to take the peripheral blood glucose sample. This must be done at the same time or just before the LP, before may be the best option, as it is easy to forget it after having just performed an LP on your patient. At the very least do a finger prick blood sugar test. The “F” in CSF should remind you to take the Fluoride oxalate for glucose...and the “S” should remind you to take the peripheral blood for “Sugar”...glucose!

Once the 5 samples have been taken telephone the microbiology laboratory (or biomedical scientist out of hours) to let them know the samples are coming, then arrange for the samples to be sent to the laboratory immediately. This is an urgent sample which should ideally be processed within 2 hours. At night most microbiology laboratories operate an on call service where the biomedical scientist (BMS) has to come in from home in order to process the sample. If you don’t tell them about the sample, they won’t know to come in and process it. Likewise, wait until you actually have the sample in your hands before telephoning just in case you fail to get the sample for some reason (there is nothing more irritating to a BMS than to get out of bed and drive 20mins into work at 3am in the morning to find no sample waiting for them!) Most microbiology laboratories suffer from shortages of these highly skilled and experienced BMS staff. If they are called in at night they are often not available to work the next day therefore making chronic staff shortages even worse.

What do you get from your urgent CSF sample?

The microbiology laboratory will perform red and white blood cell counts as well as looking at a Gram film. The biochemistry laboratory will perform a protein and glucose test. The microbiology laboratory will then put up a series of agar plates inoculated with the CSF to see if anything grows, which can take 24-48 hours and so this is not part of the urgent result.

The red blood cell (RBC) count is performed on the 1st and 3rd samples of the CSF (microbiology sends the 2nd sample to biochemistry, see below), so that a comparison can be made to distinguish a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) from blood introduced into the CSF from accidentally hitting a blood vessel on the way into the back with the needle. If the patient has had a SAH then there will be the same amount of blood in the 3rd sample as the 1st and the RBC count will be the same. If it is a traumatic tap then the blood will be much less in the 3rd sample, as the CSF washes it out of the needle.

Next the microbiology laboratory will count the number of white blood cells (WBC) in the 3rd sample to indicate whether there is inflammation. They use the 3rd sample as it gives a more accurate count if there is blood in the samples. In a sample with no blood in it, the normal amount of WBCs in a CSF sample is <4x106/L, however if blood is present this needs to be taken into account. Blood has WBCs in it therefore you need to allow 1 WBC per 600 RBCs (the normal ratio of WBC:RBC in whole blood).

This total WBC count result is further broken down into an estimate of the percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes. This is called a differential WBC count and helps distinguish bacterial from viral meningitis. How? Well, in general, bacterial meningitis is associated with raised neutrophils (which recognise and kill extracellular organisms, like bacteria) whereas raised lymphocytes are associated viral meningitis (viruses are intracellular, they need to be within a cell to reproduce, and lymphocytes recognise these infected cells). Listeria monocytogenes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are exceptions to the general rule; these bacteria cause raised lymphocytes because they are intracellular.

Distinguishing viruses from the bacterial exceptions?

The biochemistry laboratory performs protein on the 2nd sample of CSF and glucose analysis on the both fluoride oxalate tubes (CSF and blood). Bacterial infections are associated with high protein levels (bacteria produce proteins) and low glucose levels (bacteria use glucose for energy). Normal protein in uninfected CSF is <0.4g/L and normal glucose is >50% of peripheral glucose. Although you have to have taken the peripheral glucose in order to assess this! “The F is for Fluoride oxalate and S is for blood Sugar glucose!” You can’t do a correct CSF without them!

However, what if you did forget to take the peripheral glucose sample!? Then you may sometimes still tell if CSF glucose is abnormal based on the normal range of blood glucose (this only works in patients without diabetes). The lower limit of normal range of peripheral glucose is 4mmol/L and therefore the normal range of CSF glucose is >50% of this i.e. >2.2mmol/L. If the CSF glucose is <2.2mmol/L then it is low and in keeping with a bacterial meningitis. This is not best practice.

So to distinguish bacterial lymphocytes from viral you look at the protein and glucose. If the protein is raised, and the glucose low, then it is bacterial meningitis rather than viral even if the lymphocytes are raised. Viral meningitis tends to have normal protein and glucose.

Microbiology laboratories will perform urgent Gram stains on CSF samples, and if positive they are extremely useful. This is because each of the bacterial causes of meningitis has a distinctive Gram appearance, and there is no overlap. Therefore if the BMS tells you the Gram film is positive, the causative bacteria can be deduced.

So why do I need culture results?

You get a lot of information from the urgent results of a CSF sample. You can tell if the patient has meningitis if they have a raised WBC count. You can tell if it’s bacterial or viral based upon the differential WBC count and the protein and glucose. You can even know the cause if the Gram film is positive. So why culture the sample?

A positive culture tells you more about the causative bacteria than just the name. A positive culture also allows you to perform antibiotic sensitivities in order to guide the choice and duration of further treatment.

In summary, a correctly taken CSF can help diagnose meningitis and distinguish the causative microorganisms:

- Raised white blood cells indicate meningitis

- Neutrophils and lymphocytes suggest a bacterial or viral cause

- Protein and glucose confirm bacterial or viral

- Gram films if positive indicate the causative microorganism

- Culture confirms the causative microorganism and guides the choice and duration of treatment

RSS Feed

RSS Feed